Show

Show

Show

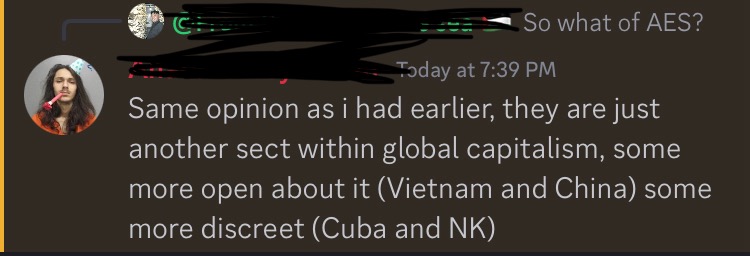

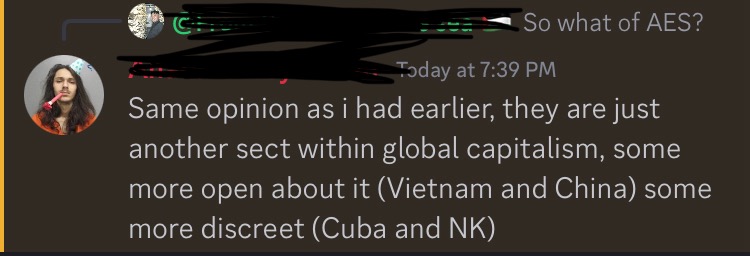

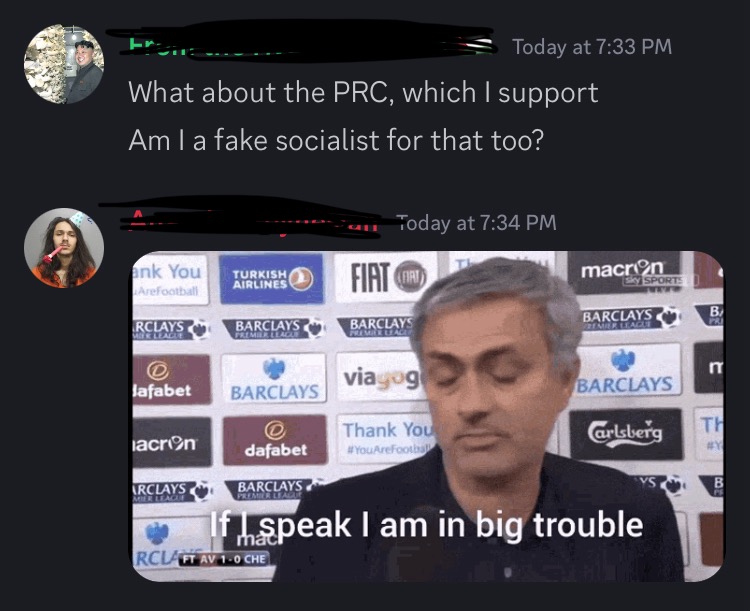

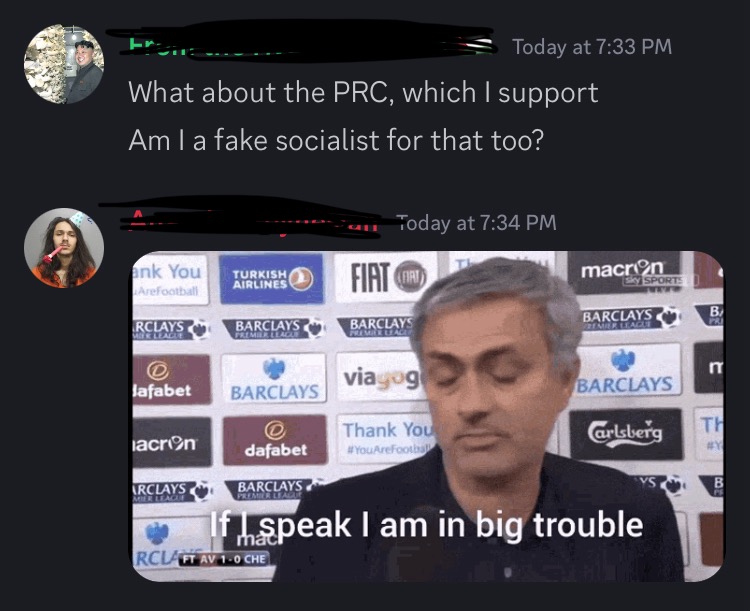

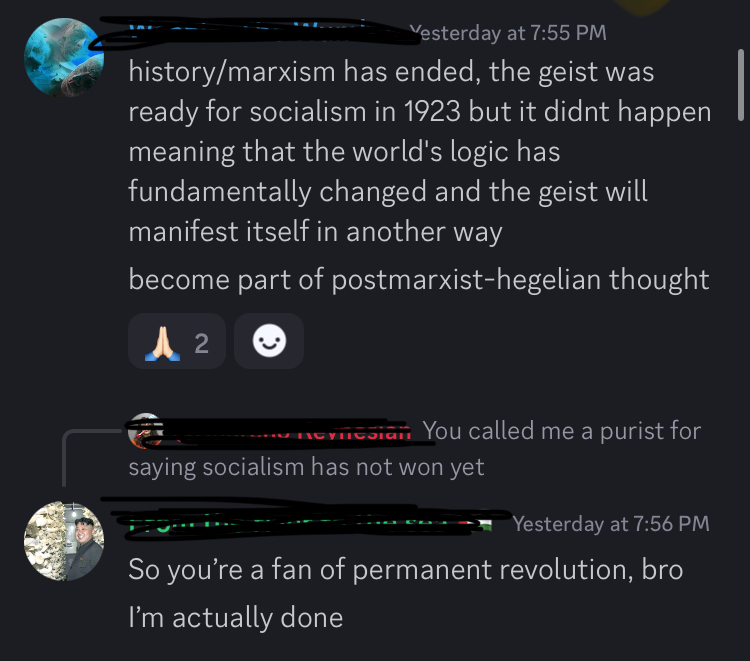

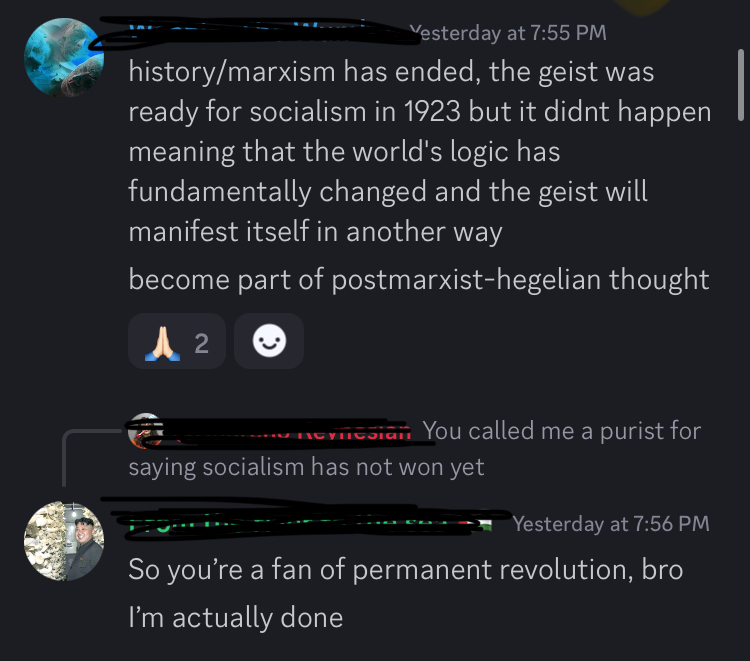

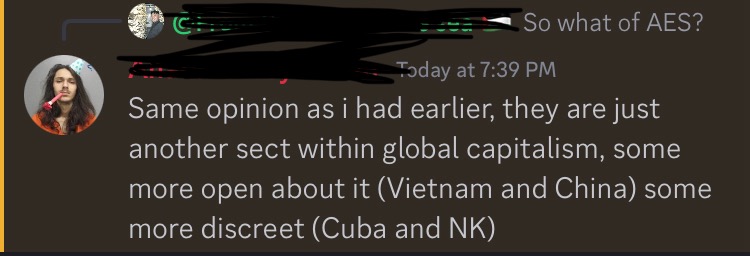

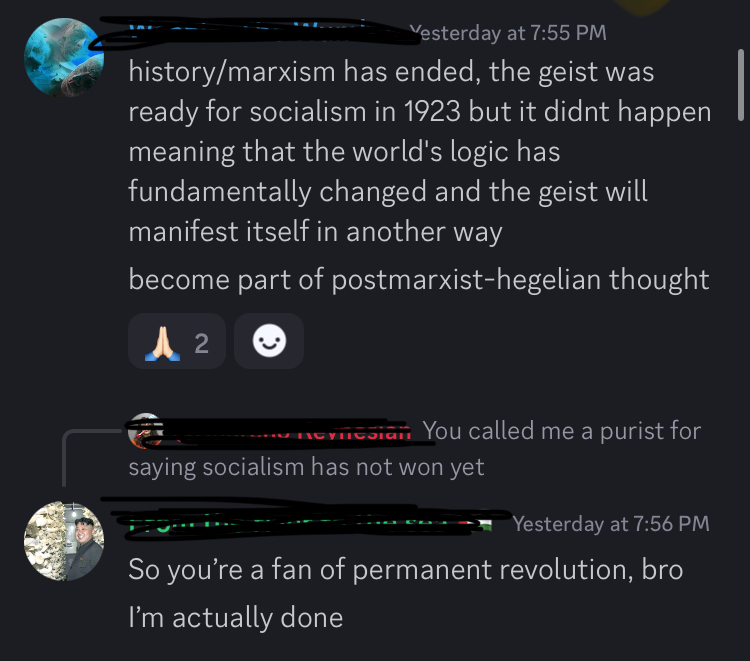

This is what you get when you constantly promote zizek.

Edit: there’s a reason why marxists don’t use hegel’s dialectics

This is what you get when you constantly promote zizek.

Edit: there’s a reason why marxists don’t use hegel’s dialectics

This guy is a personification of the defeatist Eurocentric Western left. Just sad. If he actually read works by Marxists, he would have had all his questions answered.