-

A study found a 129% increase in deforestation within Indigenous lands in the Brazilian Amazon between 2013 and 2021.

-

As a result, an estimated 96 million metric tons of carbon was released in the atmosphere during that period.

-

Researchers attribute the trend to illegal extractive activities, cattle ranching and land grabbing by invaders and some Indigenous people.

-

Though the amount of deforestation within Indigenous territories is still small compared to deforestation outside of them, the study authors say reducing deforestation in these lands should be a priority to guarantee the rights of Indigenous peoples and help Brazil meet its forest conservation goals.

Despite being among the best safeguards against deforestation in Brazil’s Amazon Rainforest, Indigenous lands saw a sharp increase in deforestation over the past decade, according to a study published recently in the journal Nature. Between 2013 and 2021, deforestation in these ostensibly protected territories increased by 129%, leading to the release of 96 million metric tons of CO2 into the atmosphere.

![]()

Full article here

The study attributes the trend to illegal mining, logging and cattle ranching by invaders, as well as the participation of some Indigenous people in these activities.

Even so, Indigenous lands accounted for less than 3% of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon, with rates of forest conservation similar to those of other protected areas. And across South America, lands in the Amazon managed by Indigenous communities tend to be carbon sinks, removing 460 million metric tons of carbon per year.

The study sought to verify whether there was a significant trend — either an increase or decrease — in deforestation rates inside and outside 232 of the 496 demarcated Indigenous lands in Brazil.

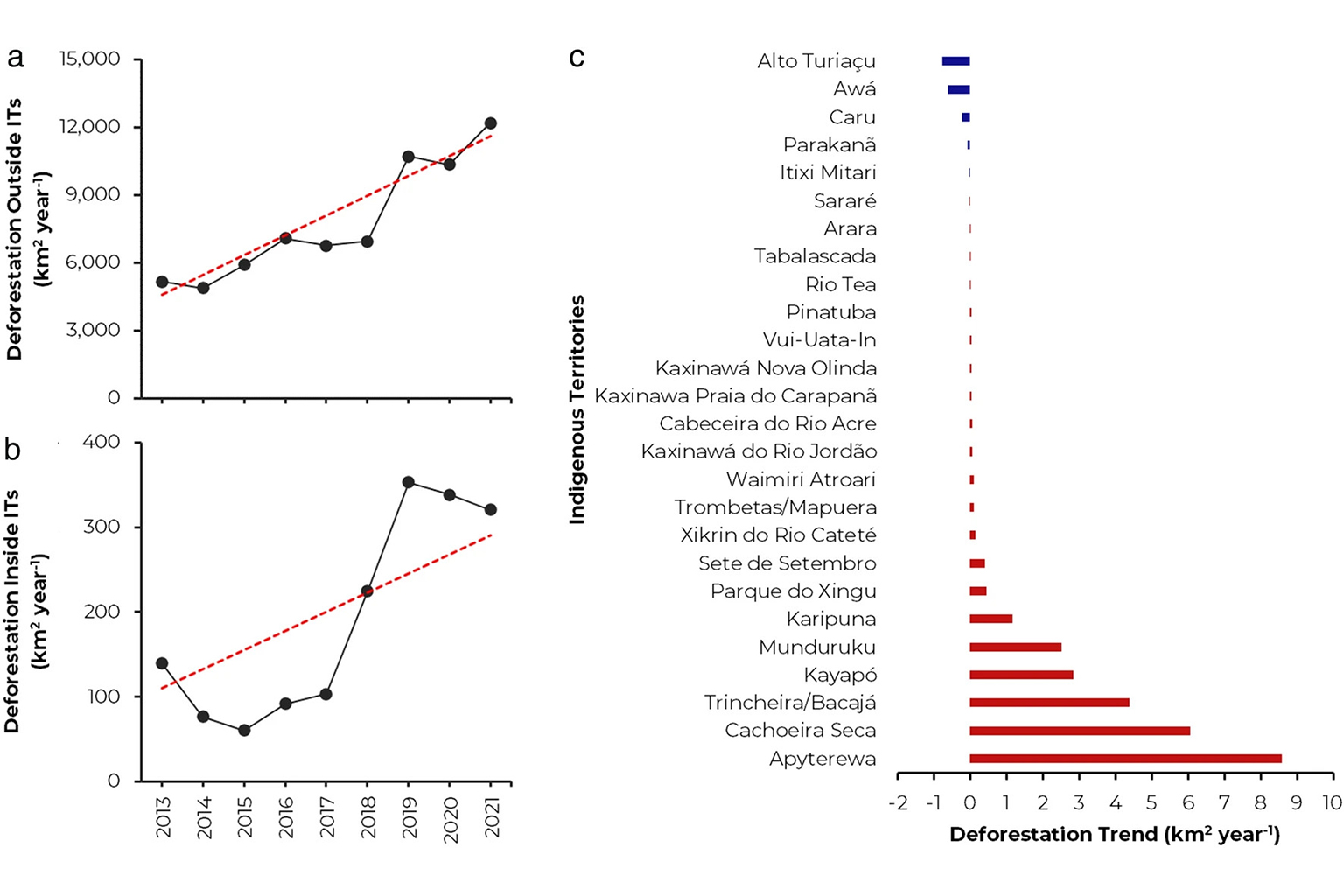

The team of scientists found that 97 of these territories saw an increase in deforestation, while 25 saw a decrease and 109 didn’t show any trend. In total, 1,708 square kilometers (659 square miles) of forest was cleared in these territories, or an area nearly the size of London.

“In absolute numbers, the devastated area in the Indigenous lands may seem small, but, as it is a region destined for environmental protection, the magnitude of the impact is much greater,” said lead author Celso H.L. Silva-Junior, a professor of biodiversity and conservation at the Federal University of Maranhão (UFMA). “The Indigenous lands were not supposed to have emitted anything, just sequestered carbon from the atmosphere.”

The numbers are even more remarkable when divided into two periods: deforestation hit a high between 2019 and 2021, when 1,012 km2 (391 mi2) of forest was lost, compared to 696 km2 (269 mi2) between 2013 and 2018.

“Since 2013, we witnessed environmental policies being gradually dismantled as a result of changes to the Forest Code, approved by the Senate in 2012, such as the reduction of [obligatory conservation] of legal reserve areas [on rural private properties] and amnesty to deforesters that acted before 2008,” Silva-Junior told Mongabay.

“However, that dismantling process intensified during the previous government.”

Under the presidency of Jair Bolsonaro, in office from January 2019 until December 2022, the federal government encouraged mining and logging in the Amazon, including on Indigenous lands — an act that’s explicitly prohibited by Brazil’s Constitution. The Bolsonaro administration dismantled environmental agencies and slashed budgets for operations to fight environmental crimes. During this period, deforestation across the Brazilian Amazon amounted to 35,193 km2 (13,588 mi2).

The increase in deforestation within Indigenous lands mirrored the trend seen outside of them, which the study put at 137%.

“The results overturned our hypothesis. We expected that, as these are areas destined for environmental protection, the Indigenous lands would not present a significant trend towards deforestation, or would be a trend towards a reduction in deforested areas,” Silva-Junior said.

Demarcated Indigenous territories bar entry to outsiders, extractive activities and infrastructure projects, meaning they should in theory be bulwarks against deforestation and a means of achieving Brazil’s forest conservation goals. However, this hasn’t stopped a wave of invaders, mostly illegal miners and loggers, from entering certain Indigenous territories.

One of the most prominent cases is that of the Yanomami Indigenous Territory, where hundreds of Yanomami died from disease, malnutrition and violence following the invasion of illegal miners.

(a) Annual deforestation outside indigenous territories between 2013 and 2021 in the Brazilian Amazon biome. (b) Annual deforestation inside indigenous territories between 2013 and 2021 in the Brazilian Amazon biome. (c) Indigenous territories with a significant deforestation trend (p < 0.05) between 2013 and 2021. Image courtesy of Silva-Junior et al. (2023).

Illegal activities go deeper than thought

The five Indigenous territories with the highest rates of deforestation were the Apyterewa, Cachoeira Seca, Trincheira/Bacajá, Kayapó and Munduruku lands. All of them are located in Pará state. The Kayapó and Munduruku territories in particular are being devastated by mining, which has led to wide-scale mercury contamination and environmental destruction.

“[Deforestation] happened with the weakening of delimited Indigenous lands as an instrument for the exclusive use of traditional communities, and with the feeling that those boundaries would eventually be changed,” said Ane Alencar, director of science at the Amazon Environmental Research Institute (IPAM). “When we look at where the invasions and the illegal mining problems were occurring in Indigenous lands, it is areas that have seen an increase in deforestation.”

Using the DETER database, the Brazilian space research institute’s monitoring system for the Amazon, the scientists found a 14% increase in the number of deforestation notices (formerly called alerts) in areas with illegal mining activity between 2016 and 2021.

The analyzed data show another trend: the advance of deforestation from the edges toward the interior of the Indigenous lands increased by 30% from the 2013-2018 period to the 2019-2021 period.

“The data shows deeper penetration into these territories, rather than small advances to the edges by neighboring farms,” Philip Fearnside, head researcher at the National Institute for Amazonian Research (INPA), who was not involved in the study, told Mongabay. “And unlike deforestation, logging is not easily detected by satellites, and was not addressed in the study.”

He added, “The numbers on illegal mining are significant because the impacts on Indigenous lands go far beyond deforestation. There are physical and cultural destruction of Indigenous peoples, sedimentation of watercourses, mercury pollution, elimination of the fish and game animals that feed them.”

When dividing the total amount of emissions released from Indigenous lands, 96 million metric tons, by the number of Indigenous people covered in the study, 700,000, the findings are also significant. It puts their carbon footprint at 4.1 metric tons per person per year.

“That is a lot of emissions: the figure usually cited for the U.S. emissions, for example, is 5 tons of carbon per person per year,” Fearnside said. “The bulk of deforestation in those territories is not done by Indigenous peoples, but by invaders. Although there are some cases of Indigenous collaboration in the illegal leasing of land to farmers.”

The damage caused by these emissions to the global climate is an urgent reason to act, although the damage to Indigenous peoples is an even greater reason, he said.

Impacts on Brazil’s environmental goals

As Brazil strives to meet its 2030 forest conservation and climate goals, the study says curbing deforestation in Indigenous territories must be a priority for the Brazilian government, as these territories serve as a means to meet its targets.

The authors of the paper listed several recommendations to prevent the advance of deforestation in these areas. Among them are the strengthening of enforcement institutions, prioritizing the protection of Indigenous lands with a significant trend of increased deforestation, and the creation of buffer zones of 10 km (6 mi) between Indigenous lands and areas of mineral exploration or high-impact projects. These buffer strips are already in use around other protected areas, such as national parks and ecological stations, to shield them from human pressures.

There are no studies yet on deforestation rates within Indigenous lands since 2021. Indigenous activists and environmentalists have expressed hope that under the new president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who has prioritized meeting conservation and climate goals, there will be a decrease of deforestation in Indigenous territories.

Since Lula took office at the start of 2023, satellite images from INPE show the rate of deforestation across the entire Amazon has fallen significantly in the first six months of the year compared to 2022, and is at its lowest since 2019. Alerts for illegal mining in the Yanomami Indigenous Territory have also hit zero for the first time since 2020, according to satellite monitoring by the Brazilian Federal Police.