The question itself might be misleading here. Considering Marx's dialectic was derived more from Hegel, the beter question would be 'how is there a contradiction inherent in concrete labor?'

So - how is that?

Here's the way I'm approaching the question. First, I'm disposing of the thesis-antithesis-synthesis and I'm replacing it with concrete-negative-abstract.

That is to say, there is a contradiction inherent in the concrete, and through the 'negative' process (the mediation process, the process that 'transforms' into the new, the sublation), we arrive at the abstract.

Where does Marx differ in his dialectic here? I know he critiqued both the Young Hegelians and the Hegelians in general for a similar problem. I'm still working out the details here...

On to the 'labor' question: concrete labor is based on the social divison of labor, into separate tasks (i.e., welding, farming, selling shirts, knitting sweaters); abstract labor is general form of labor, the aggregate sum of all labor activities.

Since I'm still uncertain on the differences between Hegelian and Marxist dialectics, I could be wrong on my assumptions following to the next issue.

Is the 'negative' in this case the labor process? Concrete labor, each specific role, is divided up for commodity production. When those commodities are put to market under capitalism (where the commodity form dominates), they meet a common exchange, the universal money-commodity. This is the basis of alienation and commodity fetishization.

Then through the labor process/valorization, labor is passed into its abstract form.

What am I getting wrong here? What exactly is the inherent contradiction? Is it that concrete labor has no value without entering capitalist relations (under an economy of generalized commodity production)? Since labor-power itself must have both a use- and exchange-value?

Or am I way off base?

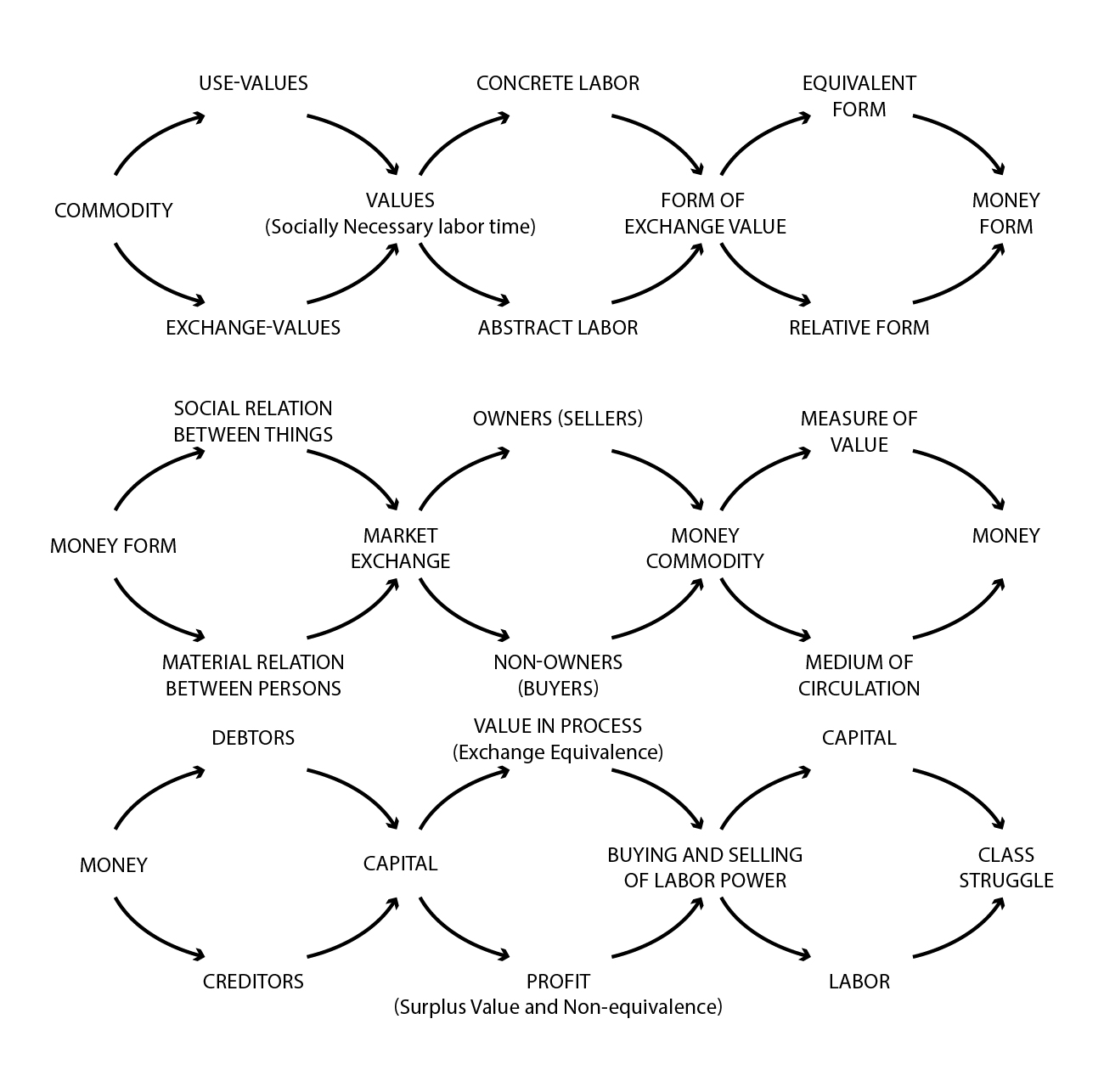

There's a great diagram from David Harvey that charts the dialectic movement throughout Marx's Capital. It helps to see that there are many, or chained, Thesis-Antithesis-Synthesis movements that build on one another. One thing that he points out is how our needs are many but our abilities few, thus we enter into a social relation of production and exchange. Because of this social nature, we must do the impossible (comparing apples to oranges, very literally) thus we arrive at Socially Necessary Labor to mediate, which creates the next link.

Show

I saved this post a few days ago so I could review before responding.

It might be helpful if you clarify the origin of your question. Why did you pose it in that particular way? I ask because I don’t recall any passages from Marx stating that concrete and abstract labor are in contradiction. I’m also not sure how you get from this first question to the second question, which assumes that there is an inherent contradiction in (the concept of) concrete labor.

While the connection from Marx to Hegel is undeniable, one has to question how useful it is to attempt reading Marx as a strict application of Hegel’s “method”. Marx made enough modifications such that it’s just easier to understand Marx in his own words rather than the words of Hegel, because in the first place, we have to grant Marx his own interpretation of Hegel.

Hegel starts with concepts that are immediately linked, such as Being and Nothing. These two concepts relate to each other in their own definitions, precisely in their oppositeness. And on further examination, in an attempt to find their difference in a way that is absolute and not referential to the other, one lands in a referential circle, a paradox or contradiction. This contradiction cannot be escaped from within the narrow scope of these two concepts. Only by bringing a wider view, a speculation by the thinker, can the totality of the contradiction be understood or synthesized as a new thought object of Becoming. This Becoming is the concrete in the abstract-negative-concrete paradigm, whereas we had started from the abstract concepts of Being and Nothing in an attempt to find their individual substances, ultimately finding that they share one substance or are different aspects of it.

Searching for traces of this method in Marx are not fruitless, but it can be confusing. Marx does use the terms abstract and concrete. But he doesn’t start with abstract concepts. Instead, he starts from empirical observation, or one can say the fully developed, concrete concepts as they are expressed in material reality. Marx analyzes (splits up) the concrete concept of the commodity and finds that it contains two aspects, use-value and exchange-value. These are already understood to form a dialectical unity because we started from the completed form of the commodity; we are working in the reverse direction of Hegel. Through analysis we move from concrete to abstract. And if you’ll allow me a bit of an ellipsis here, the result of this approach finds the abstract concept of value which was hidden behind the appearances of use-value and exchange-value.

Now, this discovery of value was more-or-less already done by the classical economists when Marx arrived on the scene. But as I. I. Rubin writes, the analysis of the commodity is insufficient for understanding capital. In the first line of Das Kapital Marx says that analysis is only the starting point. There is another part that the classical economists missed: after we have analysis the commodity, having moved from concrete to abstract, we must reverse direction and build up the concrete from the abstract.

Marx: “Political Economy has indeed analysed, however incompletely,[32] value and its magnitude, and has discovered what lies beneath these forms. But it has never once asked the question why labour is represented by the value of its product and labour time by the magnitude of that value.”

Through analysis of the commodity, we find that a concept of value necessarily emerges, and its content is labor. The more value a commodity has, the more labor is in it. But what kind of labor is it? We can’t say at this point, and that is what Marx considers the “chief failing” of the classical economists. In order to discover what kind of labor makes up value, we need to understand labor; not labor in general, but labor as it appears specifically in the capitalist epoch. Das Kapital is essentially this, Marx building up the abstract concepts of labor (and value) to see how and why they necessarily produce the concrete forms (commodities, exchange value, money, price fluctuations, etc) visible in material reality.

I’ll cut it off here since it’s Christmas and this is long enough already. Happy to answer more or elaborate as needed. I’ll leave with two good resources:

- I. I. Rubin’s essay on content and form of value. Invaluable explanation of some of the Hegelian influence in Das Kapital.

- Andy Higginbottom’s lectures on the Hegelian features in Capital