How the Russian Media Spread False Claims About Ukrainian Nazis By Charlie SmartJuly 2, 2022

In the months since President Vladimir V. Putin of Russia called the invasion of Ukraine a “denazification” mission, the lie that the government and culture of Ukraine are filled with dangerous “Nazis” has become a central theme of Kremlin propaganda about the war.

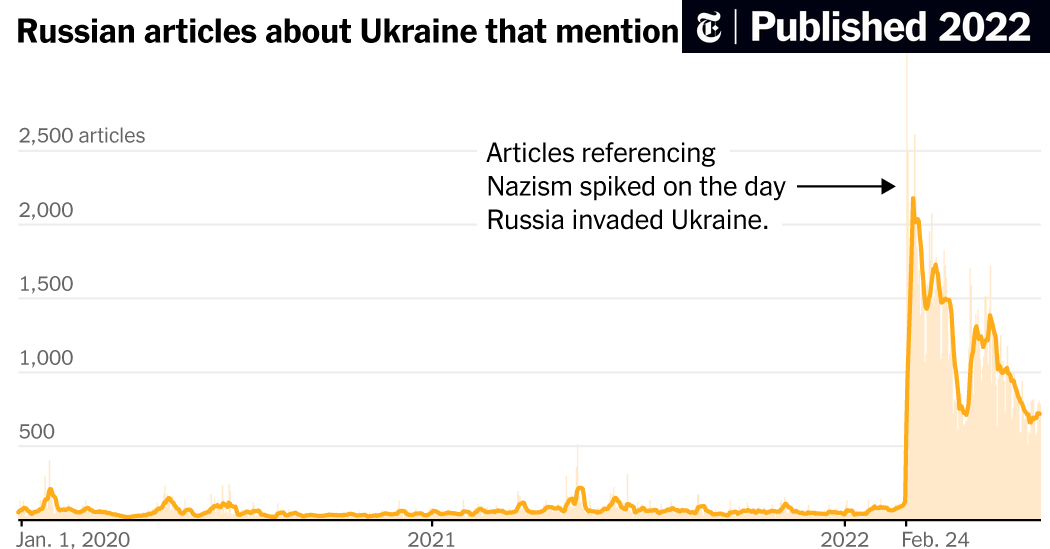

Russian articles about Ukraine that mention Nazism

A data set of nearly eight million articles about Ukraine collected from more than 8,000 Russian websites since 2014 shows that references to Nazism were relatively flat for eight years and then spiked to unprecedented levels on Feb. 24, the day Russia invaded Ukraine. They have remained high ever since.

The data, provided by Semantic Visions, a defense analytics company, includes major Russian state media outlets in addition to thousands of smaller Russian websites and blogs. It gives a view of Russia’s attempts to justify its attack on Ukraine and maintain domestic support for the ongoing war by falsely portraying Ukraine as being overrun by far-right extremists.

News stories have falsely claimed that Ukrainian Nazis are using noncombatants as human shields, killing Ukrainian civilians and planning a genocide of Russians.

The strategy was most likely intended to justify what the Kremlin hoped would be a quick ouster of the Ukrainian government, said Larissa Doroshenko, a researcher at Northeastern University who studies disinformation. “It would help to explain why they’re establishing this new country in a sense,” Dr. Doroshenko said. “Because the previous government were Nazis, therefore they had to be replaced.”

Multiple experts on the region said the claim that Ukraine is corrupted by Nazis is false. President Volodymyr Zelensky, who received 73 percent of the vote when he was elected in 2019, is Jewish, and all far-right parties combined received only about 2 percent of parliamentary votes in 2019 — short of the 5 percent threshold for representation.

“We tolerate in most Western democracies significantly higher rates of far-right extremism,” said Monika Richter, head of research and analysis at Semantic Visions and a fellow at the American Foreign Policy Council.

The common Russian understanding of Nazism hinges on the notion of Nazi Germany as the antithesis of the Soviet Union rather than on the persecution of Jews specifically said Jeffrey Veidlinger, a professor of history and Judaic studies at the University of Michigan. “That’s why they can call a state that has a Jewish president a Nazi state and it doesn’t seem all that discordant to them,” he said.

Despite the lack of evidence that Ukraine is dominated by Nazis, the idea has taken off among many Russians. The false claims about Ukraine may have started on state media but smaller news sites have gone on to amplify the messages.

Social media data provided by Zignal Labs shows a spike in references to Nazism in Russian language tweets that matches the uptick in Russian news media. “You see it on Russian chat groups and in comments Russians are making in newspaper articles,” said Dr. Veidlinger. “I think many Russians actually believe this is a war against Nazism.”

He noted that the success of this propaganda campaign has deep roots in Russian history. “The war against Nazism is really the defining moment of the 20th century for Russia,” Dr. Veidlinger said. “What they’re doing now is in a way a continuation of this great moment of national unity from World War II. Putin is trying to rile up the population in favor of the war.”

Mr. Putin alluded to that history in a speech on May 9 for the Russian holiday commemorating victory over Nazi Germany. “You are fighting for our motherland so that nobody forgets the lessons of World War II,” he said to a parade of thousands of Russian soldiers. “So that there is no place in the world for torturers, death squads and Nazis.”

A key feature of Russian propaganda is its repetitiveness, Ms. Richter said. “You just see a constant regurgitation and repackaging of the same stuff over and over again.” In this case, that means repeating unfounded allegations about Nazism. Since the invasion, 10 to 20 percent of articles about Ukraine have mentioned Nazism, according to the Semantic Visions data.

Experts say linking Ukraine with Nazism can prevent cognitive dissonance among Russians when news about the war in places like Bucha seeps through. “It helps them justify these atrocities,” Dr. Doroshenko said. “It helps to create this dichotomy of black and white — Nazis are bad, we are good, so we have the moral right.”

The tactic appears to work. Russians’ access to news sources not tied to the Kremlin has been curtailed since the government silenced most independent media outlets after the invasion. During the war, Russian citizens have echoed claims about Nazism in interviews, and in a poll published in May by the Levada Center, an independent Russian pollster, 74 percent expressed support for the war.

Part of what makes accusations of Nazism so useful to Russian propagandists is that Ukraine’s past is entangled with Nazi Germany.

“There is a history of Ukrainian collaboration with the Nazis, and Putin is trying to build upon that history,” Dr. Veidlinger said. “During the Second World War there were parties in Ukraine that sought to collaborate with the Germans, particularly against the Soviets.”

Experts said this history makes it easy for the Russian media to draw connections between real Nazis and modern far-right groups to give the impression that the contemporary groups are larger and more influential than they are.

The Azov Battalion, a regiment of the Ukrainian Army with roots in ultranationalist political groups, has been used by the Russian media since 2014 as an example of far-right support in Ukraine. Analysts said the Russian media’s portrayal of the group exaggerates the extent to which its members hold neo-Nazi views.

Russian television regularly featured segments on the battalion in April when members of the group defended a steel plant in the besieged city of Mariupol.

“For Russia, it was a perfect opportunity,” Dr. Doroshenko said. “It was like, ‘We’ve been smearing them for so long and they’re still there, they’re still fighting, so we can justify our tactics of destroying Mariupol because we need to destroy these Nazis.’”

Russia’s false claim that its invasion of Ukraine is an attempt to “denazify” the country has been criticized by the Anti-Defamation League, the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum and dozens of scholars of Nazism, among others.

“The current Ukrainian state is not a Nazi state by any stretch of the imaginiation,” Dr. Veidlinger said. “I would argue that what Putin is actually afraid of is the spread of democracy and pluralism from Ukraine to Russia. But he knows that the accusation of Nazism is going to unite his population.”

https://www.britannica.com/place/Ukraine/The-Poroshenko-administration