WASHINGTON (AP) — Two U.S. Navy SEALs are missing after conducting a nighttime boarding mission Thursday off the coast of Somalia, according to three U.S. officials.

The SEALs were on an interdiction mission, climbing up a vessel when one got knocked off by high waves. Under their protocol, when one SEAL is overtaken the next jumps in after them.

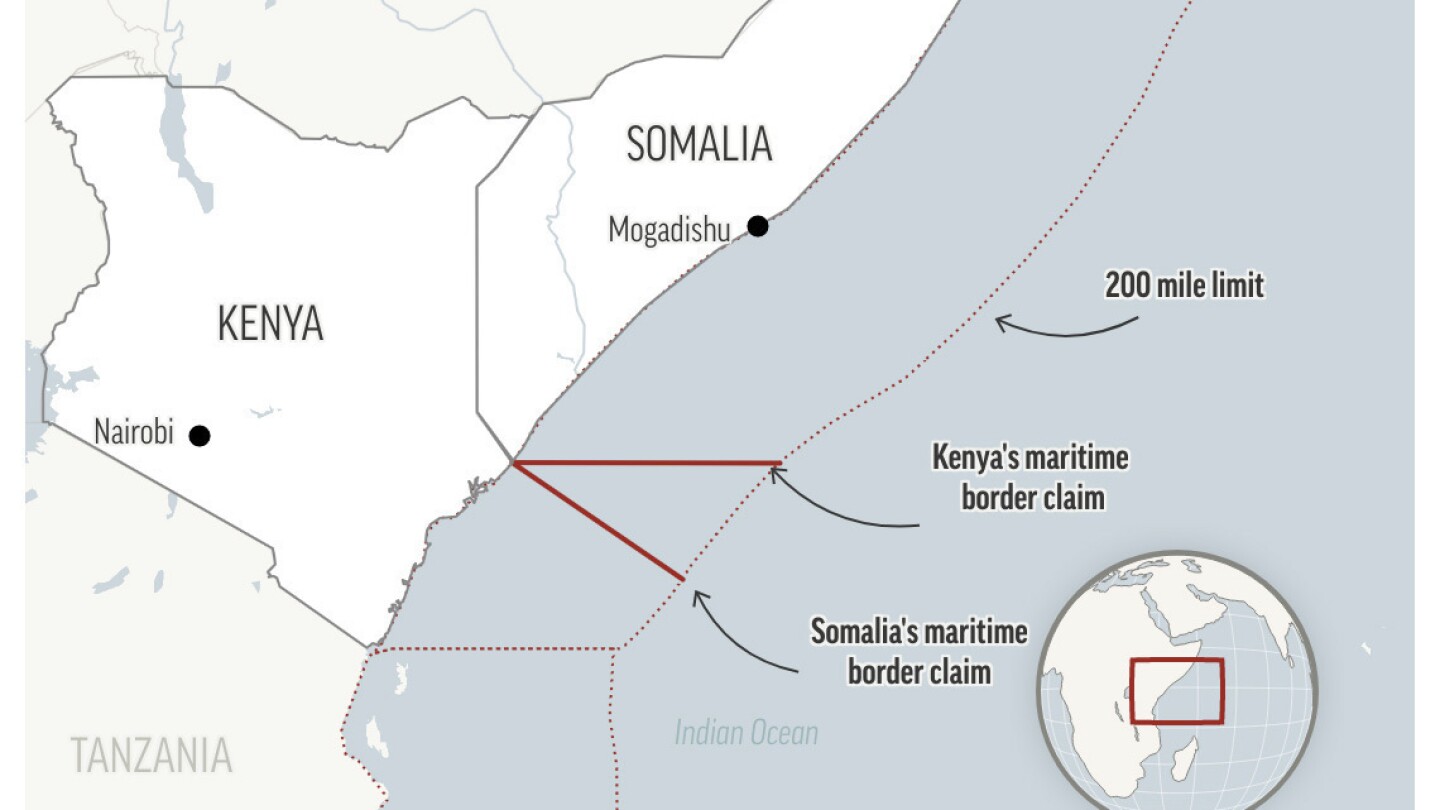

Both SEALs are still missing. A search and rescue mission is underway and the waters in the Gulf of Aden, where they were operating, are warm, two of the U.S. officials said.

The U.S. Navy has conducted regular interdiction missions, where they have intercepted weapons on ships that were bound for Houthi-controlled Yemen.

Weapons on ships boud for Yemen...?

But I thought Iran controlled the Houthis. What is this way off the coast of Somalia in their disputed maritime border with Kenya? Seems a bit out of way for a shipment from Iran.

Cover up the unspoken mercenary war we've been funding and arming for the last decade that no one talks about blame Iran without mentioning because we already programed people to associate Houtis with Iran.

Also we hope you all forgot about that 7 countries in 5 years memo from the Project for a New American Century 9/11 oopsie daisy thing that included Somalia.

Archive beyond the paywall -

In Kenya, soldiers traumatized by the U.S.-backed war in Somalia often face discipline instead of treatment cw shhh war PTSD

I found a YouTube link in your comment. Here are links to the same video on alternative frontends that protect your privacy: