cross‐posted from: https://lemmygrad.ml/post/3435504

With a rapidly growing urban population, due both to natural increase and a much accelerated immigration flow, expected to reach 35,000 in 1933, it was estimated that at least 17,000 to 18,000 further rooms were urgently required. To meet this demand, a considerable increase in building activity took place—in Tel Aviv and Haifa, building output increased fivefold.

The consequences of this building boom16 were immediate and predictable: building costs shot up; land values soared; a chronic labor shortage was especially felt in the building industry, and skilled tradesmen were at a premium; and, despite a growing emphasis on the local production of building materials, critical shortages generated an enormous increase in the importation of building materials—especially cement, timber, and structural steel—from overseas.17

Much of this material, as we have noted, was imported from [the Third Reich], by means of the transfer agreement. Both in Palestine and in [the Third Reich]18 the realization grew that the crisis conditions in Palestine housing produced at least a potential market for prefabricated housing, for which the technical infrastructure already existed, as we have shown, in [the Third Reich], and for which the transfer agreement could provide the necessary financial framework.

So despite—or because of—the tragic situation that had begun to envelop German Jewry, the strange chapter in the story of the bringing of prefabs from [the Third Reich] to the [former] land of Israel began to unfold.

[…]

At the end of June 1933, […] a column of miscellaneous information […] drew the attention of its readers to the phenomenon of the copper house in [the Third Reich], in which, it claimed, there had recently been shown a strong interest.

These copper houses had been exhibited at the Berlin Building Exhibition and had also won a Grand Prix at the Paris Colonial Exhibition, thus demonstrating their suitability for subtropical climes. After giving a detailed technical description, the Judische Rundschau concluded by stressing that the copper house “is very light to transport, and can be erected in a few days.”19

We may regard this editorial note as preparing the ground for an advertisement in the same issue—the first of a series extending to the end of the year—inserted by the Deutsche Kupferhaus Gesellschaft.20 This first advertisement is directed in general terms to the intending emigrant: the copper house will give him a very good capital investment in the fastest and best of building systems, well insulated against heat and cold.

In July the advertisements become more specific: take your own copper house to Palestine—they advise the emigrant—and you will dwell in cool spaces despite the great heat. From mid‐July therefore the “Kupferhaus” is linked explicitly to the settler in Palestine.

[…]

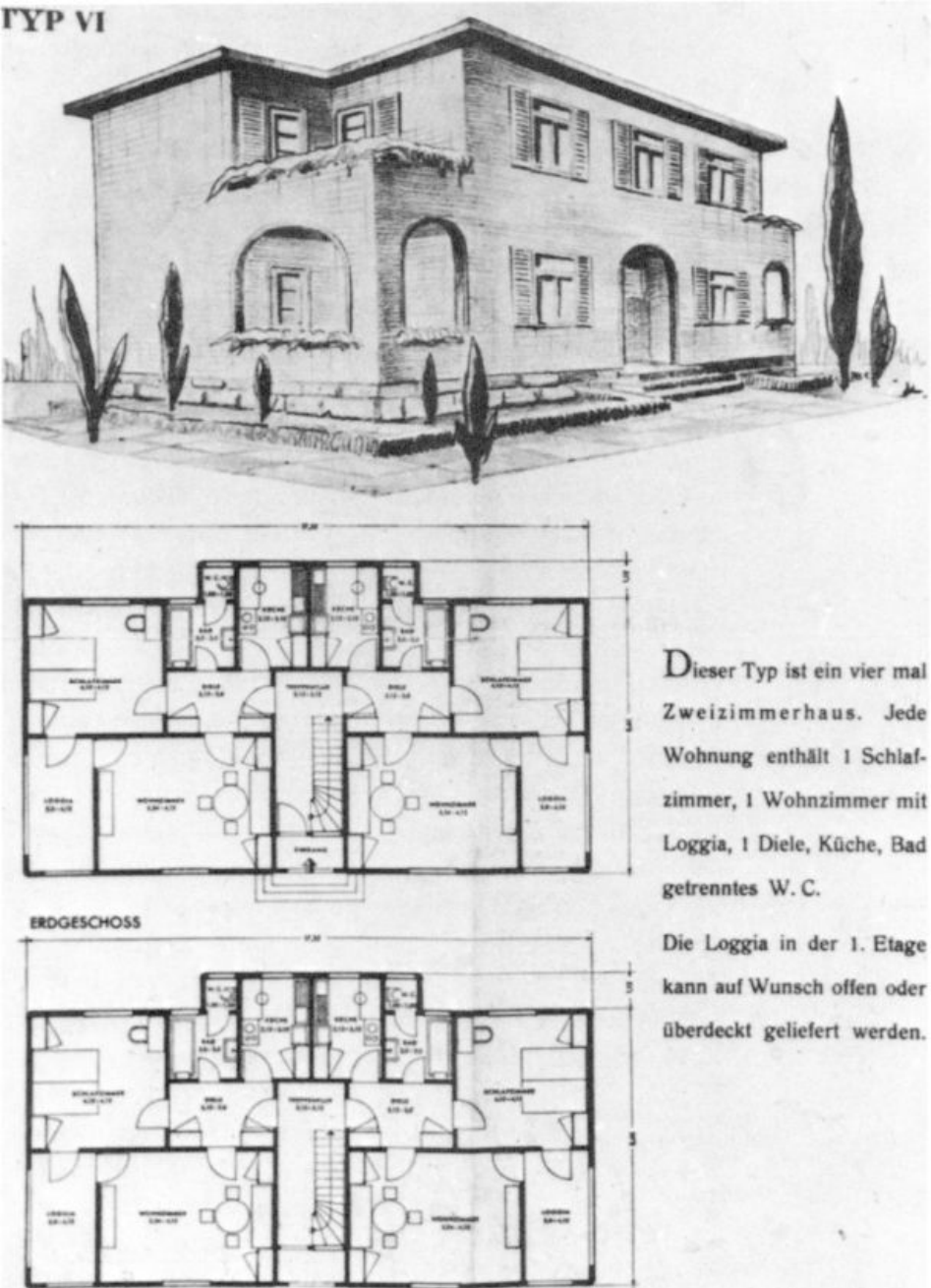

It is significant that only two of the six models are for one‐family houses (the standard house type in the original catalog), and the remainder are multiple dwelling units, ranging from two to four dwellings per building. This probably reflects a policy change resulting from a knowledge of the housing situation in Palestine, with its emphasis on small dwellings for letting purposes attracting high rentals. The ownership of one of these multiple dwellings would then assure the emigrant not only instant shelter but a steady source of income.

The needs of the local market, and local conditions, have clearly been taken into consideration and—as the catalog points out—the details and construction were specifically modified to suit Palestine, with respect to solar insulation, flyscreening, and other protective devices. The Kupferhaus company was prepared to make arrangements for shipping and charged a surcharge of 4 percent for packing for sea transportation.

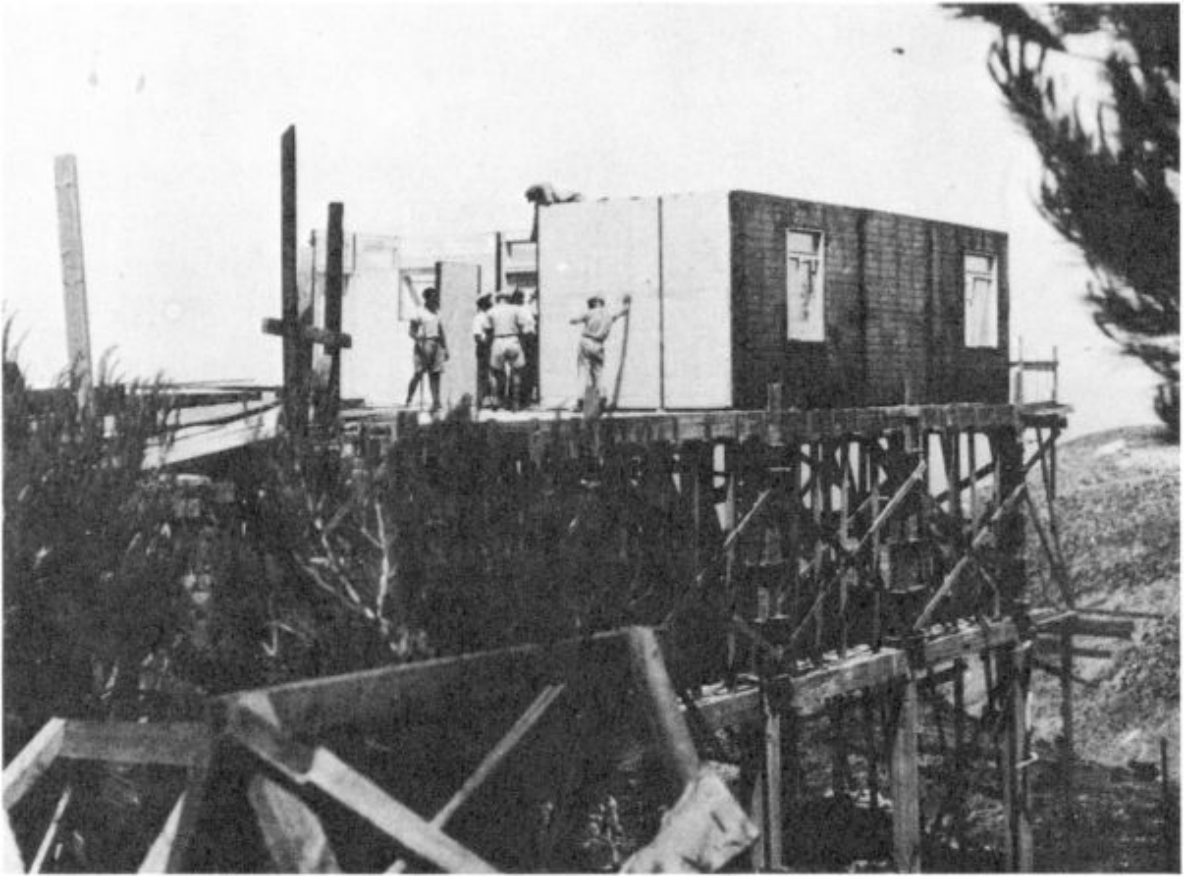

Their comprehensive arrangements did not end there, however: the catalog promised that a local agent would be appointed to see that proper specialists were available to erect the houses.

[…]

The houses […] have undergone alterations, in various degrees, throughout the many years of their use: additions have been made, internal partitions altered, space under the supporting concrete platforms filled in, in one case a roof replaced. They have now stood for nearly fifty years, continuously occupied, often with a minimum of care and maintenance.

Within these limits, and where the original specifications were adhered to,35 all the existing houses are in remarkably good condition for their age, and they still provide comfort conditions in extremes of heat and cold that make them desirable residences.

(Emphasis added.)

Notice how accommodating these houses were (and still are): relatively easy to establish, specialists available for establishment, well suited to a diversity of climates, a steady source of income, and so forth. This was part of the Fascist bourgeoisie’s plan to make Palestine more attractive to European Jews: the better Palestine looks, the likelier Jews are to get the hell out of Europe and stay out. That is how severely the Fascist bourgeoisie wanted to separate Jews from Europe.

This particular exportation of resources might seem trivial given that the number of prefabricated buildings sent from the Reich to occupied Palestine was relatively small (‘perhaps only 20 or 25 buildings containing about 100 dwellings’), but that was to be expected given the buildings’ experimental nature, which made many potential customers uneasy about purchasing them. The significance that this has to us, as anti‐Zionists, is that it proves that the Fascists were willing to go to the market with a mostly untested product if it meant accelerating Jewish emigration.

Show

Pictured: A prefabricated building’s plan.Show

Pictured: ‘Deutsche Kupferhaus Gesellschaft, Tuchler house, Haifa, construction photo, 1934’Further reading: