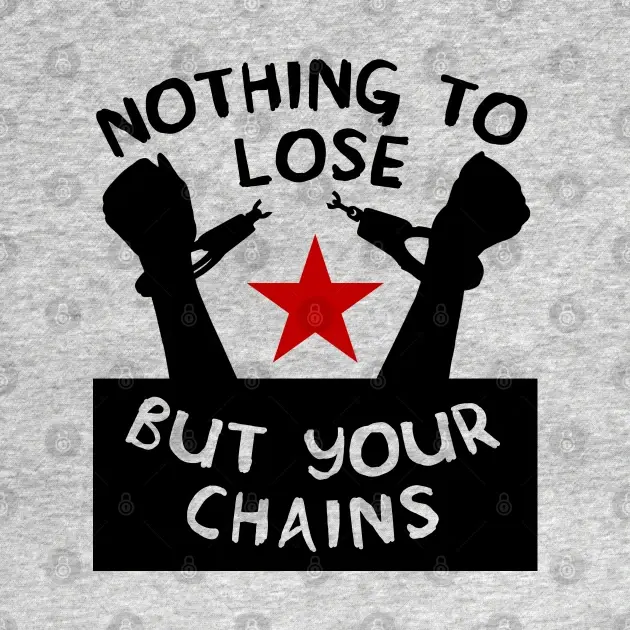

Direct FB link. TLDR: A lesson in real time that power, not money, is at the heart of the capitalist system. It's easy to be a "good" boss, giving your workers good pay and benefits. Much harder to share power.

I'm trying to produce a more formal statement about it but bottom line is: I screwed up badly and did not live up to my values. I feel bad because I think I've generally done a good job for five years of making Current Affairs a pretty ethical organization and in a single day I bungled it and disappointed a lot of people. I've got a lot of work to do to rebuild trust, but I'm not sure if CA will survive, as subscribers rightly feel betrayed and we're getting cancelations. I don't blame people who cancel, all I can say is that I tried hard for five years to do right by people who worked for us and I'm really sad that I undid it in a single week.

Even though I screwed up, the truth is more complex than the 'fired the staff for wanting democracy' narrative. I've done many egalitarian things with Current Affairs. I don't earn any more than anyone else (we all get $45k a year). I gave up ownership over it, and don't make any kind of profit from it. Anyone can tell you I don't order people about. Everyone works when they like. I've hardly ever exerted authority over it internally at all. Partly as a result, the organization developed a kind of messy structurelessness where it wasn't clear who had power to do what and there was not much accountability for getting work done. The organization had become very inefficient, I wasn't exercising any oversight, and we were adrift. I did feel that it badly needed reorganizing. Our subscription numbers had not been doing well lately and I felt I needed to exert some control over the org to get it back on track, asking some people to leave and moving others to different positions. Unfortunately, I went about this in a horrible way that made people feel very disrespected, asking for a bunch of resignations at once and making people feel like I did not appreciate their work for the organization.

The charge made in the statement by staff is that I didn't want CA to be a worker cooperative. I think this is complicated, or at least that my motivations are somewhat explicable. A worker cooperative had been floated as one of the possible solutions to the structurelessness problem. I am not sure my position on this was defensible, it might have been deeply hypocritical and wrong and selfish, but I will at least explain how I felt. **Since starting CA, I have resisted making Current Affairs 'owned' by staff not because I want to own it myself but because I don't want it to be owned at all, I want it to operate as a not for profit institution that does not belong to particular people. ** ow, I don't want to be a workplace dictator, and I think nobody can say that before this I acted like one in my day-to-day work, but I do feel a strong sense of possession over the editorial vision and voice of the magazine, having co-founded it and worked at it the longest. I had been frustrated at what I saw as encroachments on my domain (editorial) by recently-hired business and admin staff. I had also been frustrated that people were in jobs that clearly weren't working. Plans that were discussed for making the organization more horizontal in its decision-making seemed like they would (1) make it impossible to fix the structurelessness problem and exacerbate the problem of lack of oversight/accountability/reporting structure (2) make it less and less possible for me to actually make the magazine what I think it can be. I felt that without making sure we had the right people in jobs, this was going to result in further disorganized chaos and slowly "bureaucratize" CA into oblivion. But I do not think I tried to fix that problem in the right way at all.

I have never ever tried to own CA or make a profit from it. This was not about money, or keeping people from getting their rightful share of the proceeds. I am not a capitalist, I do not expropriate surplus value. I have never taken more money for myself than anyone else on the full-time staff got, and want to do everything possible to ensure fair working conditions. What I did want was the ability to remain the executive director of the organization and be able to have staff report to me so as to make sure stuff was getting done. That may have been wrong. But that is how I felt.

I am open to believing that this cannot be justified. I can say where the feeling came from which is: for years I made the magazine basically alone in my living room, and I have felt like it is my baby and I know how to run it. It was hard to feel like I was slowly having my ability to run it my way taken away. I think that it's easy to talk about a belief in power sharing but when it comes down to actually sharing power over this thing I have poured my heart and soul into, it felt very very difficult to do. I found it easy to impose good working conditions and equal pay. Giving up control over running CA was a far harder thing for me to accept. This is a personal weakness that ran up against my principle.

I am sorry to all of you and to the staff of CA who did so much to make it what it is today. It's my sincere hope that CA makes it through this because I think we have much more great work to do in the future. I will try my very best to make sure this is done in accordance with sound leftist values. This was not that.

That is his framing, but if we're going to read his story critically (as we should) then we have to read the other side critically as well. I see a lot of people taking the other side as the gospel truth but finding all sorts of places to be skeptical of this. That's not a good way of sorting through disputes.

I don't think it's about clout -- what clout is there to be had at CA in the first place? It looks closer to him being (or at least seeing himself as) more committed than anyone else and not trusting people he sees as less committed with a project he's put so much effort into.

deleted by creator

I don't know. It's a small, divided community, and I'd say more people know of Briahna Joy Gray (a former CA contributor or editor) than him. Hell, most people here only "know" him because they like to rip on his clothes and voice (totally how we should treat other leftists, but that's a different discussion).

...because she was Bernie's Campaign Press Secretary, not because of CA

That's the point. CA itself is not a big deal and BJG has more "clout" than NJR by doing non-CA stuff.

NJR had built up a decent amount of respect because of CA, much more so than other writers for the publication because he was the face of it. The example of BJG doesn't change that. Bernie's campaign isn't just some random stuff outside of CA , his 2 campaigns have been the impetus for a rebuilt left in America. So yeah, you get more clout in a notable role on his campaign than just about anywhere else. That doesn't disprove that NJR got a good amount of clout from building and running CA.

In a labor dispute there are 2 sides: the boss and the workers. I'm going to believe the workers every time, especially when they explicitly say the boss is lying, but you do you.

That's true in a capitalist enterprise, but this isn't a capitalist enterprise. The boss is doing as much actual work as anyone (and likely more) and getting paid the same low salary. No one is extracting surplus value from anyone else's labor.

That's what makes this so interesting: it's a case study of a workplace disagreement in a non-capitalist organization. You can't default to the easy answers in a typical workplace dispute because it's far from a typical workplace.

As long as he retained hiring and firing power, along with the editorial control that he had, then it was a capitalist enterprise. The equality of pay may lessen the surplus value extracted by the boss, but by maintaining those power dynamics his workers are still alienated from the product of their labor. They wanted a co-op model to have a much more democratic say over those processes, and when his control over that was materially threatened for the 1st time, beyond just saying it would be great to have workplace democracy!!, he lashed out and fired everyone.

This is a boss vs worker dispute. The equal pay doesn't change the power dynamics.

Actual co-ops have individuals with hiring and firing power, so that alone doesn't make a business a capitalist enterprise. The touchstone is whether someone is extracting surplus value from others' labor, and there's no evidence of that. He doesn't even own the business, and it's structured such that no owner can skim off whatever profits are generated (it's a not for profit).

Could it be more democratic? Absolutely. But there are degrees to this stuff, it's not just purely capitalist or socialist.

Who are democratically decided, sure. Even if it's true that there was no surplus value extracted it doesn't matter because the workers are still alienated from the product of their labor. When they attempted to have more democratic control over the process of making the magazine, they got fired. Sounds like a capitalist boss worried about losing control, to me.

As someone who's worked in the non-profit sector, trust me when I say that this means basically nothing. These set-ups can often become even more exploitative because they're generally set up to do work that people consider "good," like organizing workers or fighting climate change. But regardless, the pay isn't the issue here. It's about power dynamics and how the boss reacted when the workers attempted to organize to change those power dynamics.

I agree it's not a co-op with democratic management, but that doesn't make it capitalist, necessarily. There are types of unfairness or inequality that don't amount to capitalism. To your point about how non-profits can be exploitative by taking advantage of people's enthusiasm to do "good" work, that's true, but I think "exploitative" only fits if you have a person doing the exploitation. If no one is reaping any benefit above $45k/year, it sounds like a group collectively deciding to prioritize the project over pay. It might not be the best decision for everyone, but it's not as if one person is depressing everyone else's wages to that one person's benefit. There are bad situations that don't amount to exploitation.

There are also some interesting questions here about how (or if) the amount of democratic input one gets should vary with their work contribution, and what should be done if workers don't appear to be willing or able to effectively mamage the workplace collectively. Say you're a bricklayer. You work ~200 days per year, and nine other bricklayers at the company each work 1 day per year. Does everyone get one vote? If the nine people with small contributions don't appear to be willing or able to manage the company, should they still get to? Whatever contribution discrepancy existed wasn't anywhere near this stark, but the example highlights some of the legitimate questions that could arise in a more realistic situation.