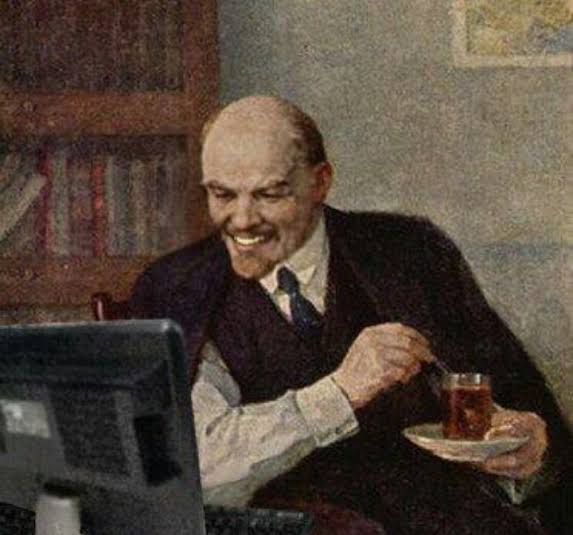

Sorry for the bad picture I kinda scrambled to get it, but yeah my prof went fully into the whole "in communism you don't own your toothbrush" stuff and then put up this slide.

I'm glad that my webcam and mic was off because I couldn't stop myself from rolling my eyes at that.

edit: idk why the pic is rotated and idk how to fix it

But really defining capitalism in a rigurous way is an important very hard question.

Is merchant capitalism from the early modern period suficiently diferent from other forms of primitive acumulation to be called capitalism? Is it about city dwelers? Then is abbassid khorasan capitalist?

Is it about some measures of market develooment and unification? Then is 1200s england capitalist as greg clark uses analisis on grain prices to confirm it was very integreted market?

Is the distinction about diferent acounting conventions?

Is it about enclosure and proletarization? Then isnt tenancy the end result of such a proces?

Isit about the disapearence of customary rigths in favor of state driven legibilizaton of laws? Then capitalism would be about state power.

Is it about diferent forms of capital such as land and machinery becoming indistinct? Then we can only speak of capitalism after 1860.

It's a really huge question to be answered in such a simplistic way, for a bit more context the class is about media literacy and the lecture was on advertising and consumerism.

Like even if I was trying to describe capitalism in lay terms I'd go into more detail than that.

I think the more conventional Marxist approach is the switch from C-M-C to M-C-M. Once that algorithm of capital seeking to create more capital takes off, then you've got something I would call capitalism, although that definition certainly wouldn't map to all uses of the term.

But i think that type of aquisitivnes is an inherent human trait. Hunter gatherer societies are often limited by their prodictive forces. Other times they police themselves. But as soon as you get to pastoralism you find these patriarchs hoarding thousands of cattle and other productove forces simply for the sake of amassing wealth.

I think amassing personal wealth is a distinct economic phenomenon from an MCM circuit in a market economy. In most pastoral societies I'd argue the situation is complicated by other strong social forces, and part of the distinct thing about capitalism is that it really is capital breaking free of existing human structures and institutions and reorganizing them according to it's own need for growth. All that is solid melts into air, etc.

I agree there are other social forces acting on pastoralist societies and others. But tbe same can be said of today.. modern societies have their myths and rituals that influence behaviour other than capital. These often reinforce capitals interests but not necesarily. The same can be said from institutions in a pre industrial society that in many cases tend to justify the status of the ruling class.

As for capital reorganizing strucrures. Arent all human institutions organised to maximize economic output in a given context?

When does it become capital instead of a the vast personal wealth of a roman patricisn. Who owns a significant amount of it in stocks of diferent companies?

Yes there are other social forces today, but I think the point is that capital - not billionaires, monarchs, celebrities, or patriarchs - is in the driver's seat.

All human institutions? That's a strong claim unless you have a very narrow definition of "human institution". Just like we agreed above - there are other social forces at play, and many of those have corresponding institutions. Any of them large enough to involve large amounts of people across larger regions usually have to be part of a capitalist world in many ways, i.e. raise funds or participate in a market or something, but that doesn't mean they're all organized to maximize economic output. Also, I'd count everything from big decentralized activist networks down to my little book club as human institutions, and many of those have no economic input or profit whatsoever.

The vast personal wealth of a Roman patrician doesn't circulate in a production economy and is far more fixed to the person/family than capital. Capital is not wealth but wealth with a kind of agency, ripping across the social and economic landscape corralling potential productive forces into it's sway. Capital can't just exist; it has to grow by continuing to circulate and pick up more exploited labour or it goes into crisis.

In a strange dark way capital is like life, a weird algorithmic quirk in a natural space that picks up speed and size through self-replication and mutation. Part of the problem is that the sheer causal power of large pools of capital that have tendrils all across the globe is way stronger than any individual or even individual nation-states, hence the calls for international proletarian solidarity and organization.

I don't know specifically about Rome, but in the patrician's case their wealth is likely more under their control to do with as they please. At the same time it probably comprises a wide array of different kinds of assets, many of which I would assume spend more time travelling vertically through heritage or other lineages than horizontally across the market.

For me personally, I tend to think of it as there are no absolute hard lines around defining any mode of production because it's all dialectical. It's true for capitalism and socialism. Marx himself talks about how the feudal MoP and capitalist MoP operated alongside each other - impacting each other dialectically - for centuries. Most of us here would agree that China and Vietnam are socialist. However if you just spend a week in a Chinese city with an open mind but not really any Marxist knowledge, you're going to have a hard time distinguishing what makes it socialist and not capitalist. And the approach the CPC takes appears to be that someone in that city would have a hard time distinguishing when it no longer seems very capitalist.

All the questions you ask are great. But I think they highlight how the development of capitalism came about at all of those stages.

I think this is the correct answer. Human societies are ver complex and there are many modes of production in use at any given time. There has always been a type of capitalist production. But was limited either by production technology(an agrarian energy source) or customary rigths.