Feature Song: Marquee Moon by Television (February 8, 1977/Elektra Records/New York, NY)

I'm sure it's a phrase you've heard before, but the first time it was uttered was in January of 1977, when UK punk fanzine writer Mark Perry wrote it in Sniffin Glue. It was just after The Clash signed a deal with CBS Records for £100,000. That a band so rampantly anti-establishment as The Clash would bow to the wishes of a major label for any money was a betrayal of what punk was all about. With The Clash, The Sex Pistols, and The Saints all on major labels, it was clear that punk was just a fad and now the architects were cashing in. Never mind that The Ramones and The New York Dolls were both on major labels, for UK punks , it was DIY Or Die. And so it came to pass that punk itself had to die.

What an appropriate end to the story, right? It came out of nowhere in mid '75 and burned a trail through 1976 before crashing and exploding into a blaze of glory in '77. It feels so fitting that the genre with songs that rarely lasted over 2 minutes should burn out in a little under 2 years. But that's not what really happened.

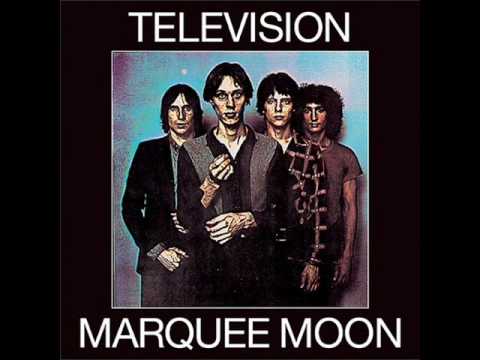

Remember Television? Those guys who used to play in the kitchen at the Mercer Arts Center and then made it cool to play weird rock at CBGB? Well despite being arguably the founders of this new scene and getting record label attention since '74, they waited until August of 1976 to finally sign a contract. They had recorded some demos with Brian Eno for Island Records in 75, but the results left much to be desired. Eventually they signed with Elektra records in August of '76, under the condition that singer/guitarist Tom Verlaine could produce the record himself. Elektra was nervous, as all the other labels were, about signing a punk band, let alone giving them controls on an album. Eventually they agreed on the condition that Tom produce the album with help from a sound engineer. In the time it took for Television to sign a record deal, they had strayed from the more abrasive sound of their early years. Layered power chords were out, intricate almost jazzy solos were in. Short, sharp material was out, too, as some tracks play out more like extended jams than punk anthems. The feature track, off their debut album, is almost 10 minutes long and features TWO guitar solos. Marquee Moon released on February 8th, 1977 to critical acclaim, with magazines on both sides of the Atlantic giving five-star ratings. However, critics at the time didn’t know how to categorize Marquee Moon. It was certainly weird like those punk kids down at CBGB, but it had a certain pop sensibility. It wasn’t punk, but listening to it you get the feeling that punk had to have happened in order for this to come about. It was like...Post-Punk.

This development was sort of a long time coming, as Blondie had started adding synthesizers to punk in ‘75. They still followed that sped-up 60s bubblegum pop formula the Ramones were still perfecting, but they relied less on the abrasive guitar sound. They still covered topics not often covered in mainstream music, strongly influenced by Debbie Harry’s staunch feminism. In other words, despite being softer, they were still punk. Similarly, Talking Heads took even more of the edge off of punk, opting for an acoustic guitar sound in their earliest days . By the time they recorded the 77 album, their sound owed less to The Stooges and the Ramones and more to Parliament-Funkadelic and Fela Kuti's work with Ginger Baker . However, the core of their lyrical content still revolved around anti-capitalism and the importance of taking control over your own life. Ditto for even earlier punk acts like Suicide and The Patti Smith Group . Basically, in 1977, punk was still more about attitude than sound, and some artists were starting to disassociate with the term.

Making things worse was the popular misconception that punk was inherently scary. Sure, acts like the Ramones and the Sex Pistols were awful loud and often sang about unsavoury subjects. But overall, they were more goofy than scary. But all that sex and violence and anti-capitalism that had made record labels hesitant to sign punk bands also made record stores hesitant to stock punk albums. Despite the critical acclaim these records may have received, it was often quite hard to get your hands on them if you didn’t live in a city with a punk scene. That’s when people caught onto something Malcolm McLaren had been saying in the press. In the wake of the Sex Pistols bringing punk to the UK, a number of acts sprung up who agreed with the anti-authority bent, but didn’t want to be so abrasive about it. These acts include Elvis Costello and The Attractions , The Jam , and Ian Dury and The Blockheads along with a number of bands previously under the pub rock label like The Stranglers and Dr. Feelgood. Former Sex Pistol Glen Matlock even played a role in his second band, Rich Kids. Malcolm McLaren had described these groups as the ‘new wave’ of punk acts, seeing as they had come up after the first wave of the Sex Pistols, The Clash, and The Damned. This term was also seen as evoking the French New Wave of cinema in the late 50s and early 60s, which eschewed corporate studio financing and structure to pursue experimental projects. These ideals mapped onto those of these new punk bands almost perfectly, and many began to identify with the label more than they did with punk. This led to the “Don’t Call It Punk’ campaign in 1977, where Sire Records, home of many CBGB bands, sought to get the public to stop calling this music punk rock. It was all to be New Wave from here on out.

In short, punk rock was doing the one thing it promised it would never do. It was growing up. And much like what happened when Rock & Roll grew up in the mid 60’s, this development had its detractors. But we’ll pick up on that next time, as we continue to navigate the schisms of punk to come.