From the article:

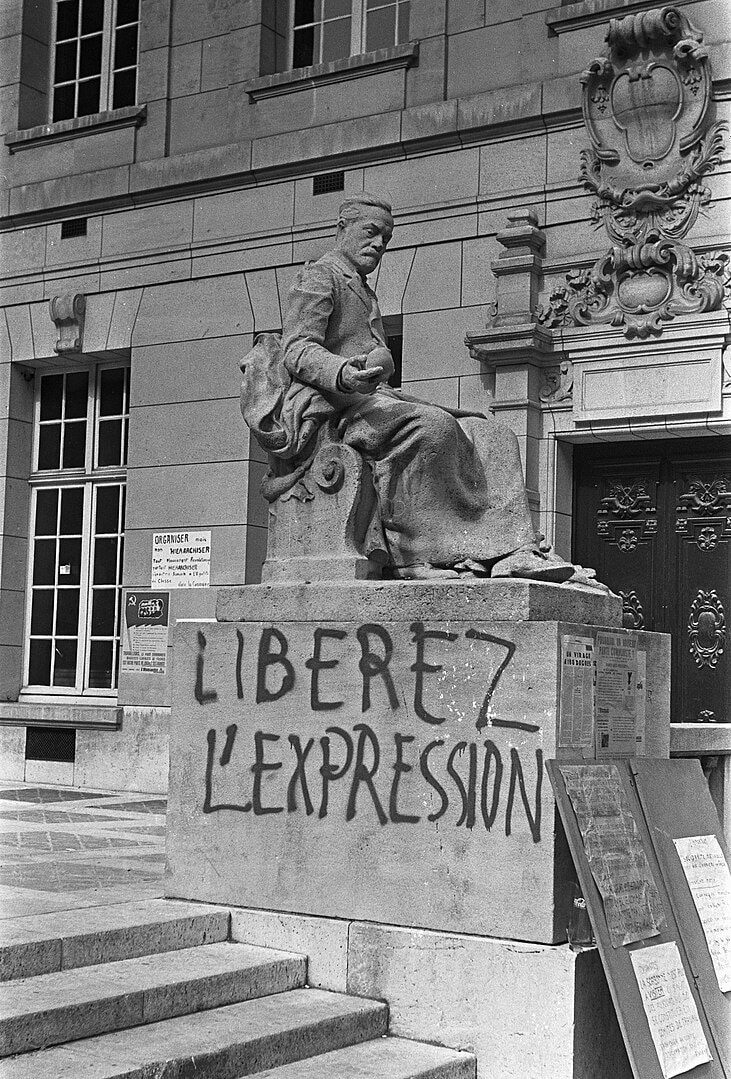

Bourgeois history has primarily retained from ’68 the spectacle of the student-led revolts in the heart of Paris: the barricades in the Latin Quarter, the occupation of the Sorbonne, the libertarian sloganeering, and so forth. A significant segment of the intelligentsia, particularly anarchist, Maoist, Trotskyist, libertarian socialist, and Marxian currents, wrote in support of these revolts and often joined them in the streets and the various occupations. Marxist-Leninist intellectuals generally questioned the strategic clarity of the unorganized petty-bourgeois and anticommunist politics of many of the more vocal students, which they criticized for being gauchistes and beholden to the illusory belief in a revolutionary situation.5 At the same time, many of these intellectuals also recognized the youth uprising as an important catalyst for a new phase of class struggle, and they stalwartly supported the mobilization of workers.

These different segments of the intelligentsia, as we shall see, were not those that rose to global prominence as major contributors to the phenomenon known as French theory.6 On the contrary, those marketed as the ’68 thinkers—Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida, Jacques Lacan, Pierre Bourdieu, and others—were disconnected from and often dismissive of the historic workers’ mobilization. They were also hostile to, or at least highly skeptical of, the student movement. In both senses, they were anti-’68 thinkers, or at a minimum, theorists who were highly suspicious of the demonstrations. Their promotion by the global theory industry, which has marketed them as the radical theorists of ’68, has largely obliterated this historical fact.

Yes, the left wing in France, or what is seen as the left in terms of the intellectuals mentioned in the article that the author has disdain for, regressed since 68. France since then has acted as an auxiliary force for US hegemony with it's project in Africa.

Amazingly put.