The pineapple (Ananas comosus) is a tropical plant with an edible fruit; it is the most economically significant plant in the family Bromeliaceae.

The pineapple is indigenous to South America, where it has been cultivated for many centuries. The introduction of the pineapple to Europe in the 17th century made it a significant cultural icon of luxury. Since the 1820s, pineapple has been commercially grown in greenhouses and many tropical plantations.

Pineapples grow as a small shrub; the individual flowers of the unpollinated plant fuse to form a multiple fruit. The plant normally propagates from the offset produced at the top of the fruit or from a side shoot, and typically matures within a year

History

Etymology

The first reference in English to the pineapple fruit was the 1568 translation from the French of André Thevet's The New Found World, or Antarctike where he refers to a Hoyriri, a fruit cultivated and eaten by the Tupinambá people, living near modern Rio de Janeiro, and now believed to be a pineapple. Later in the same English translation, he describes the same fruit as a "Nana made in the manner of a Pine apple", where he used another Tupi word nanas, meaning 'excellent fruit'. This usage was adopted by many European languages and led to the plant's scientific binomial Ananas comosus, where comosus 'tufted', refers to the stem of the plant. Purchas, writing in English in 1613, referred to the fruit as Ananas, but the Oxford English Dictionary's first record of the word pineapple itself by an English writer is by Mandeville in 1714

Precolonial cultivation

The wild plant originates from the Paraná–Paraguay River drainages between southern Brazil and Paraguay. Little is known about its domestication, but it spread as a crop throughout South America. Archaeological evidence of use is found as far back as 1200 – 800 BC (3200–2800 BP) in Peru and 200BC – AD700 (2200–1300 BP) in Mexico, where it was cultivated by the Mayas and the Aztecs. By the late 1400s, cropped pineapple was widely distributed and a staple food of Native Americans. The first European to encounter the pineapple was Columbus, in Guadeloupe on 4 November 1493. The Portuguese took the fruit from Brazil and introduced it into India by 1550. The 'Red Spanish [es]' cultivar was also introduced by the Spanish from Latin America to the Philippines, and it was grown for textile use from at least the 17th century.

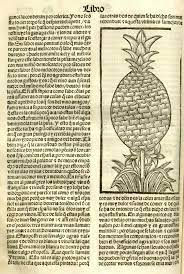

Columbus brought the plant back to Spain and called it piña de Indes, meaning "pine of the Indians". The pineapple was documented in Peter Martyr's Decades of the New World (1516) and Antonio Pigafetta's Relazione del primo viaggio intorno al mondo (1524-1525), and the first known illustration was in Oviedo's Historia General de Las Indias (1535)

Old World introduction

The pineapple fascinated Europeans as a fruit of colonialism. But it was not successfully cultivated in Europe until Pieter de la Court developed greenhouse horticulture near Leiden from about 1658. Pineapple plants were distributed from the Netherlands to English gardeners in 1719 and French ones in 1730. In England, the first pineapple was grown at Dorney Court, Dorney in Buckinghamshire, and a huge "pineapple stove" to heat the plants was built at the Chelsea Physic Garden in 1723. In France, King Louis XV was presented with a pineapple that had been grown at Versailles in 1733. In Russia, Peter the Great imported de le Court's method into St. Petersburg in the 1720s; in 1730, 20 pineapple saplings were transported from there to a greenhouse at Empress Anna's new Moscow palace.

Because of the expense of direct import and the enormous cost in equipment and labour required to grow them in a temperate climate, in greenhouses called "pineries", pineapple became a symbol of wealth. They were initially used mainly for display at dinner parties, rather than being eaten, and were used again and again until they began to rot. In the second half of the 18th century, the production of the fruit on British estates became the subject of great rivalry between wealthy aristocrats. John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore, built a hothouse on his estate surmounted by a huge stone cupola 14 metres tall in the shape of the fruit; it is known as the Dunmore Pineapple. In architecture, pineapple figures became decorative elements symbolizing hospitality.

Since 19th century: mass commercialization

Many different varieties, mostly from the Antilles, were tried for European glasshouse cultivation. The most significant was "Smooth Cayenne", imported to France in 1820, subsequently re-exported to the United Kingdom in 1835, and then from the UK via Hawaii `to Australia and Africa. "Smooth Cayenne" is now the dominant cultivar in world production. Jams and sweets based on pineapple were imported to Europe from the West Indies, Brazil, and Mexico from an early date. By the early 19th century, fresh pineapples were transported direct from the West Indies in large enough quantities to reduce European prices. Later pineapple production was dominated by the Azores for Europe, and Florida and the Caribbean for North America, because of the short trade routes.

The Spanish had introduced the pineapple into Hawaii in the 18th century where it is known as the hala kahiki ("foreign hala"), but the first commercial plantation was established in 1886. The most famous investor was James Dole, who moved to Hawaii in 1899 and started a 24-hectare (60-acre) pineapple plantation in 1900 which would grow into the Dole Food Company. Dole and Del Monte began growing pineapples on the island of Oahu in 1901 and 1917, respectively, and the Maui Pineapple Company began cultivation on Maui in 1909. James Dole began the commercial processing of pineapple, and Dole employee Henry Ginaca invented an automatic peeling and coring machine in 1911.

Hawaiian production started to decline from the 1970s because of competition and the shift to refrigerated sea transport. Dole ceased its cannery operations in Honolulu in 1991, and in 2008, Del Monte terminated its pineapple-growing operations in Hawaii. In 2009, the Maui Pineapple Company reduced its operations to supply pineapples only locally on Maui, and by 2013, only the Dole Plantation on Oahu grew pineapples in a volume of about 0.1 percent of the world's production. Despite this decline, the pineapple is sometimes used as a symbol of Hawaii. Further, foods with pineapple in them are sometimes known as "Hawaiian" for this reason alone.

In the Philippines, "Smooth Cayenne" was introduced in the early 1900s by the US Bureau of Agriculture during the American colonial period. Dole and Del Monte established plantations in the island of Mindanao in the 1920s; in the provinces of Cotabato and Bukidnon, respectively. Large scale canning had started in Southeast Asia, including in the Philippines, from 1920. This trade was severely damaged by World War II, and Hawaii dominated the international trade until the 1960s.

The Philippines remain one of the top exporters of pineapples in the world.

Megathreads and spaces to hang out:

- ❤️ Come listen to music and Watch movies with your fellow Hexbears nerd, in Cy.tube

- 💖 Come talk in the New Weekly Queer thread

- 💛 Read and talk about a current topics in the News Megathread

- ⭐️ August Movie Nominations ⭐️

reminders:

- 💚 You nerds can join specific comms to see posts about all sorts of topics

- 💙 Hexbear’s algorithm prioritizes comments over upbears

- 💜 Sorting by new you nerd

- 🌈 If you ever want to make your own megathread, you can reserve a spot here nerd

- 🐶 Join the unofficial Hexbear-adjacent Mastodon instance toots.matapacos.dog

Links To Resources (Aid and Theory):

Aid:

Theory:

now all fediverse discussion will be considered a current struggle session discussion and all comment about it are subject to be removed and even banning from the comm.

have all of you a good day/night ![]()

This is a really silly question, but does anyone know some good texts about chapters in academic/non-fiction writing? It's just such a basic prerequisite that texts be organized into different sections and subsections that I don't manage to have one clever thought about it. Why do we have chapters? What are subchapters even? Is there writing outside of chapters? I would really appreciate some answers!

You know, I had never actually thought about this concept until this comment. I'm curious if anyone has a good piece of writing on it.

I'm not sure if this is what you're asking for, but maybe you could look into style guides? Although I'm not sure if something like The Elements of Style gives the rationale behind organizational decisions like that.

Length, Received Wisdom

There's a book about writing a PhD. I can't remember the name. It says a good length chapter should be about 10,000 words because it's enough to get across complex thoughts and short enough to read in one sitting without forgetting the start by the time you get to the end. I think that's a clever way of explaining such an arbitrary standard. You see 100,000 word PhDs with three uneven chapters that pass without corrections, and published academic books that are longer but equally uneven (hello, Marx), so…

One reason for having chapters e.g. in edited collections is because (1) it's cool to work on edited collections as it's an excuse to work with your friends, (2) it opens the possibility of publishing the types of articles that reviewer 2 at the prestigious journals simply hate, and vice versa, and (3) it minimises the limitations of academic freedom when trying to publish unorthodox thoughts (is that still one reason, or three?).

–

Developing an Argument

Using chapters in a monograph helps with presenting the development of the argument. Each chapter could:

Or you might have one chapter each on:

It depends on what you're writing and the conventions of your field. And on whether you have some kind of paymaster/supervisor/editor/boss that insists on doing it their way and has the power to make you.

–

Field/Discipline

While it depends on the field, it also seems that a chapter is roughly the same length as an article would be. And an article is the length it has to be so as to fit so many articles in a physical journal. This also depends on the country as US articles can be very long. Like 70k+ words. Usually it's Marxists who choose to do this kind of thing.

–

Without doxxing yourself, what's your field?

And what are you writing or planning to write? (As in, form, rather than content—book, dissertation, individual chapter, etc? Although feel free to mention the content. Again without doxxing yourself.)

Advice

A chapter can be any length, really. And you can use 'parts' to group a few chapters together. That might be stylistic as the differenve between parts/chapters/sections and chapters/sections/subsections can be unclear.

I'd say a chapter should be as long as it needs to be to deal with everything you have to say about the chapter's argument/theme. Until it gets too long. Then you try to identify multiple arguments or themes in the text and split these into their own chapters. But this advice probably doesn't help much in the abstract.

Chapters can be divided into sections, which may be determined by the discipline, setting, or content. I'd say they always need, to be trite, an introduction, main body, and conclusion.

The main body can be one section or multiple sections. The introduction and conclusion can be longer or shorter depending on how long you want the introductory and conclusion chapters to be. I'd err on the side of shorter intros for each chapter (the intro chapter itself can be as long as any other chapter).

As for chapter conclusions, you can either keep them short and summarise the main points of the chapter. Then have a rather meaty, analytical 'conclusion' chapter at the end, which puts all the summary conclusions together and ties the argument together.

Or you can end each chapter with a longer conclusion (which might be two sections when it comes to presenting the text, because the section labelled 'conclusion' 'shouldn't' include new ideas or information). This longer 'conclusion' analyses, criticises, and evaluates the material in the chapter (going beyond the kind of summary conclusion mentioned above). If you go this route, the final 'conclusion' chapter can be more of a summary of the earlier conclusion sections at the ends of previous chapters (i.e. because the bulk of the argumentative analysis is already done; and I say 'more of' to hint that a conclusion chapter should still be more than a summary—it needs to drive home the overall argument).

–

Publishers

If you look on publisher websites for advice for authors, they tell you what they expect/require. A lot of it seems to come down to money and marketing. As you might expect. The publisher decides some arbitrary guidelines for chapter length, etc, depending on what they think will sell better. Otherwise, it's up to the author to decide. Sometimes top authors can set their own terms if their book will sell, regardless. Although they'll listen to a good editor if they want to keep being a top author.

–

If I remember (or if you reply, which will serve to remind me), then when I'm at my desk I'll get you some references (depending on your answers to the above questions).