Beverley Port-Louis, a Yued woman whose ancestors worked and lived at New Norcia, said she had no knowledge of the sale "until it came out in the paper".

"You can't just continue buying land all over the place and not acknowledging traditional owners," she said.

"You've got an obligation, a moral obligation as far as I'm concerned."

Tattarang subsidiary Harvest Road said in a statement it looked forward to meeting the traditional custodians and hoped to create training and employment opportunities.

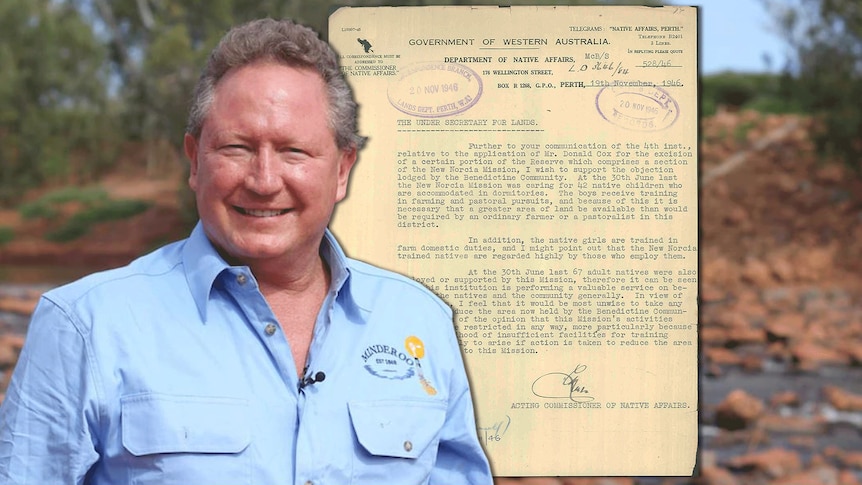

The documents, obtained by the ABC with assistance from the State Records office, show Mr Forrest's new landholding, which will be added to his growing beef cattle empire, includes part of what used to be called Reserve no 944.

The 13,000 acres were set aside "under exceptional conditions" in 1886 and leased to pioneering Benedictine monk Rosendo Salvado as part of his mission to encourage local Aboriginal people to become farmers of their land.

Historian Tiffany Shellam from Deakin University's Contemporary Histories Research Group said Salvado's vision was what secured him a growing area of land in the district in the mid to late 1880s.

"He hoped that Aboriginal people would settle down as land owners on this land, in the European sense, and he believed this would assist in their transition to become 'civilised', which was his plan," she said.

"This was always the way in which new land was acquired from the government, this promise that Aboriginal people would be using the land, cultivating and labouring on it."

Salvado built cottages for Aboriginal families on the mission land, although these have long since been demolished at the old townsite — now a tourist attraction — where a few monks still live today.

But the caveat that the reserve land would continue be used for an Aboriginal mission disappeared after 1947, when the Benedictine community decided to call in an exclusive deal Salvado had struck with the government 60 years earlier as part of the agreement to lease reserve 944.

As an "urgent" memo to the premier of the day shows, the Benedictines now wanted to buy the land which they had been leasing for one pound per thousand acres for decades.

Decades later, it had a very different focus, according to Ms Shellam.

"There was a change of superintendent at the mission when Salvado died, to Abbot Torres, who turned the interest of New Norcia away from Aboriginal residents and towards the education of Catholic settler children," she said.

Ms Shellam said the mission "orphanages" for Aboriginal girls and boys were still operating but there was tension around how they were being run.

"The adult Aboriginal people weren't allowed to come in and visit their children and a lot of tension arose around this time between past Aboriginal residents and the missionaries," she said.

"There was the example [in 1907] of 32 Aboriginal fathers storming the mission to try and see their children and being arrested by police."

Ms Port-Louis has a close connection to New Norcia, with ancestors on both sides of the family living and working on the mission farm.

She also has first-hand experience of life at the girls' institution, St Joseph's.

She was seven when she and her two younger sisters were sent there because their mother was ill and their father, who was a farm worker at a neighbouring property, also had four boys to care for. Exterior of old building on street Until it closed in 1974, between 600 and 1,000 Aboriginal girls attended St Joseph's school and "orphanage" in New Norcia.

Ms Port-Louis said she received an education, but the chores and farm work were relentless.

She remembers polishing the chapel floors with old stockings and candle wax and stripping the hair from bullock legs to make into broth as being among her weekly tasks.

She still has flashbacks to her three years at the mission.

"I'll never forget what she used to call us," Ms Port-Louis said of one of the nuns.

"She used to say oh you ... you mad black bitches."

The final straw came when a different nun bashed her so hard over the hands with a metal ruler that her fingers swelled up.

Her parents who visited that weekend took her and her sisters back to the farm after that. 'Today we've got nothing'

Looking back on her mission days, Ms Port-Louis isn't bitter about her experiences.

She said she learnt a lot from the nuns.

She is an admirer of Rosendo Salvado because, she said, he did a lot of work for Aboriginal people.

But she believes he would be "turning in his grave" over the recent sale of the farm lease.

"He [Salvado] founded that place for Aboriginal people," she said.

"And today, we've got nothing."

History shows the sale to the Benedictine community in 1950 was a critical turning point for the future tenure of the land.

Four years after World War II had ended, there were plenty of ex-servicemen looking to make a living off the land.

As a letter from the then-assistant commissioner of native affairs shows, there had already been interest from a potential buyer and the Benedictine community had had to fight to hold onto the reserve.

After extensive debate, it was decided that the government had little choice but to honour the 1886 arrangement. An act of parliament was drafted to sanction the sale for a total of 8,780 pounds, to be paid in 20 instalments.

What the deal did not include was any ongoing obligation by the Benedictines to use the land for Aboriginal use and benefit.

Historian Tiffany Shellam said that was a missed opportunity, which had lasting consequences.

"To sell it now at such huge profit, with no benefit for the Yued community or the Aboriginal community of New Norcia, I think is quite devastating," she said.

Ms Shellam pointed out that had the land remained a reserve, the Yued's native title rights would have been retained over their traditional land.

The current abbot of New Norcia, John Herbert, did not respond to requests for information about the land purchase by Mr Forrest.

Landgate searches indicate the 19,000 acres that Tattarang has purchased include only half of reserve 944, to the east of the New Norcia townsite, and not the remaining section to the west of the townsite, although the ABC was unable to confirm this with Tattarang or the New Norcia community.

According to a statement on New Norcia's website, the community regrets having to sell most of its farmland, but the proceeds are needed to help pay redress and compensation to alleged victims of historical abuse who attended the mission's Aboriginal orphanages.

The community has already made payments totalling more than $10 million to victims of abuse by monks who have died. Several claims are believed to be still outstanding.