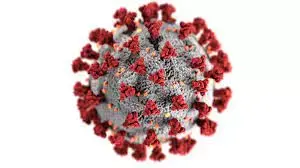

I see articles like this: https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/technology/your-immune-system-is-imprinted-with-its-first-coronavirus-exposure/ar-AA16e57s and I get kinda confused. Is it saying that getting an updated vaccine (or recent infection) will somehow c*ckblock the immune system from being able to handle a new strain?

It means upon reinfection or booster, your body will create antibodies for the first strain or vaccine you were exposed to. This was the concern with the newest bivalent boosters, early tests showed they weren't that protective (against new variants) compared to the first vaccines, but they seem to be protecting people pretty well.

It means we probably won't be able to keep boosting forever, and will have to get different vaccines, or find a work around, or target different parts of the virus to invoke a better immune response, and probably sooner than later.

You've pretty much got it.

Other seasonal alphacoronaviruses seem to have the same effect for SARS-COV-2, where the immune response is hampered if you'd previously survived an infection from either NL63 or 229E.

There's no technology at present to overcome imprinting, it's just a natural phenomenon we've known about for decades which regulators ignored when recommending a vaccine series to tens of millions of young people, based on a single spike protein subunit from a strain isolated in Wuhan in 2019, despite the prevalence of new strains with significantly different lineage at the time. You can search the modlog for my previous comment and proximity to the vaccine program.

You can search the modlog for my previous comment and proximity to the vaccine program.

Saw your comment in there but why was it deleted? No reason was given.

if you're only exposed to the h3n2 influenza virus while growing up, you lack immunity to the h1n1 virus and it will be far more deadly. The Spanish flu was h1n1, but far deadlier than the swine flu partially because the flu in the years prior to ww1 was h3n2 for a long time. Young adults had little to no immunity to it, so it killed them in greater numbers than younger/elderly people. Young people were resilient because it was their first exposure to flu, and older people had been exposed to more strains in their youth

modern flu vaccines are a cocktail to inoculate for multiple strains because different variants gain prominence each season

idk how scientists can apply this to covid because of how fast covid mutates though

Let's say you have two options: get a booster for an older variant right now or for the new variant in a month.

If you go for the older one, your immune system will get really good at making defenses against it and will be primed for a fast response if you get infected. If you run into an older variant, great! That fast response will kick ass. If you run into a new variant, slightly less great: your fast response will help a lot (good to get boosted) but your body won't properly fight the thing off until you develop a new response to its slight differences, literally the shape and sticky parts of the variant. So it may take a while to fight off, like weeks.

If you stay uninfected and get the new booster, then later get infected by a variant the new booster targeted, you'll get the fast response and it'll clear it out.

The only thing imprinting adds to this dynamic is that it's actually possible that your old variant response to a new variant limits your ability to form a new battalion of anti-new variant immune cells, just a bit.

In terms of COVID and its rapid evolution, this mostly just means that new variants are pretty effective at immune escape. In terms of protecting yourself, you have very little control over the timelines for boosters and there are too many variables to make a decision other than you should get boosted when new ones come out.