You can use the auto-generated translated captions if you want to watch. I tried to clean it up, but because the subject matter is in Russian, the core of the issue just doesn't transfer to English. Basically the dude compares a modern textbook to a textbook by Kostin from 1953. The 1953 Russian textbook starts with a straightforward exposition about stressed and stressed vowels and how to check them in the root word, and gives 10s of examples for each of the 5 vowels.

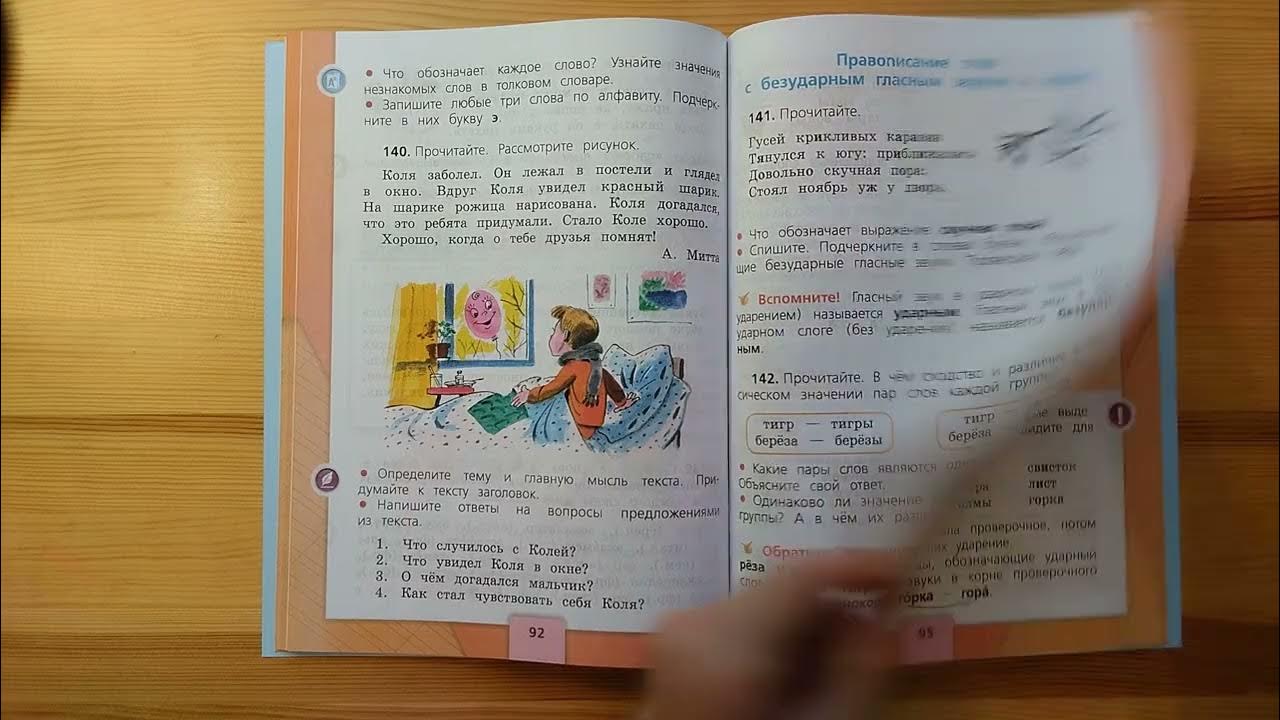

Then comes the new textbook by Kanakina and Goretskiy (the uploader includes his conjecture about why they included Goretskiy on the cover). It is overloaded with pictures, and every page has a "Remember!" and "Pay Attention!" blurb attached, which dilutes their meaning.

He then makes a point to demonstrate what he calls "inappropriate theorizing". The fat orange blurbs all have some dense wall of definitions, and they themselves are not clear. Seems like an attempt at introducing rigor that is misplaced. The other blurbs about remembering and paying attention are also written obtusely. This is a textbook for 8 year olds, if I haven't mentioned yet.

This doesn't seem to be a unique thing, many teachers in Russia and other post-Soviet countries have observed this mangling of Russian, math, and natural sciences textbooks. This video is viral on Russian internet.

Reminds me of this:

How a flawed idea is teaching millions of kids to be poor readers

She says sounds and letters just didn't make sense to her, and she doesn't remember anyone teaching her how to read. So she came up with her own strategies to get through text.

Strategy 1: Memorize as many words as possible. "Words were like pictures to me," she said. "I had a really good memory."

Strategy 2: Guess the words based on context. If she came across a word she didn't have in her visual memory bank, she'd look at the first letter and come up with a word that seemed to make sense. Reading was kind of like a game of 20 Questions: What word could this be?

Strategy 3: If all else failed, she'd skip the words she didn't know.

Most of the time, she could get the gist of what she was reading. But getting through text took forever. "I hated reading because it was taxing," she said. "I'd get through a chapter and my brain hurt by the end of it. I wasn't excited to learn."

No one knew how much she struggled, not even her parents. Her reading strategies were her "dirty little secrets."

Apparently, in the US, some teachers are not teaching the relationship between pronunciation and spelling, so some students come with these strategies (or rather, as flan pointed out, they actually teach the kids to do this).

From that article it seems theyre actually teaching those strategies. The part about disproving these ideas in the article is interesting but made me wonder why anyone thought it worked in the first place. An adult 2nd language learner could tell you they lean heavily on context in their new language but not in their native language. And i’m pretty sure it’s possible to read words in isolation. Weird stuff.

I think the idea comes from the fact that fluent adults generally do not need to phonetically decipher words letter-by-letter, but rather recognize them instantly, probably by some combination of shape and context. So memory and context is how good, fast readers actually read usually, thus when you want to teach someone to become a good reader, you may conclude that you need to teach them that. The problem is, of course, that (a) people have not actually deliberately memorized all those words, but rather, these instant brain connections have automatically formed through years and years of reading, and (b) when this strategy fails for an unfamiliar word, a good reader will very much fall back on the letter-by-letter deciphering.

This idea is perhaps more attractive for English educators, than it would be in some other language, because the relationship between spelling and pronunciation is rather more complex (or "loose") than in many other languages.

But yeah, I do wonder if these people just totally forgot how they themselves learned to read, and also, it very much flies in the face of empirical evidence.

Very interesting to see! For now I've only known that American children are terrible at reading and that the source of this is of course capitalism, but now to also see someone show things that I also know are real in Poland (that textbooks from socialist countries are miles better than what we have today), and that the sentiment of capital ruining education seems universal is veeeery nice.

It's the problem of turning everything into a market. If teaching kids how to read is a solved problem, how do you keep selling new and "improved" textbooks?

i'm not well-educated enough on child pedagogy to know for sure, but i've seen a lot of suggestion that one of the driver's of the current us dip in literacy is moving away from empirically tested methods of teaching reading. something about "sight words" vs phonics.

I went on a deep dive into that shit a while ago and it seems like things are starting to turn around but millions of kids were essentially taught to read wrong (and not as a joke :kung-pow:)

Yeah I've listened to "Sold a Story" a few months back and it was fucking astonishing to me to learn the reasons for why the US has such problems with reading comprehension. I've always heard that it is usually on the or below the level of six grade or something, but to learn precisely why was astonishing. Truly made me hate capitalism even more.

I have had some thoughts on school book production, which I may as well post here:

So, here in Germany, there are large, private publishers of school books. These are basically monopolies. They create school books based on the curriculum standards set by the government. There is a "market" in the sense that the teachers at the various schools can choose among several books that are available and approved by the ministry (assuming they get budget approval). Those publishers (e.g. Bertelsmann) are, btw, also behind lobbying efforts to open up more parts of the education system to private interests.

These books get minor updates almost every year, which are insignificant for the most part (lots of changing things around so the page numbers are off). Old editions cannot be bought. This causes confusion among teachers and students. This is, I'm pretty sure, so that the schools will buy a new full set of books every couple of years. The publishers also completely discontinue the books every now and then, and instead publish a totally new books.

The way new books are made is that they hire a bunch of teachers, and tell them to write some chapter of the book, based on the government standards. They try to do this mostly on the cheap, so there's a lot of looking at existing books while barely avoiding plagiarism. The quality doesn't actually improve over time, and there is not really much feedback from the actual teachers using the books.

If, instead, the books were made in some sort of collaborative process, by interested teachers, researchers at universities, and so on, that would improve things a lot I reckon. A bit maybe like Wikipedia or Linux, and ideally with a blanket suspension copyright for educational purposes, so that they can include whatever material they like. Of course the teachers should be paid for this work as well.