Thanks to decades of deregulation and a gush of speculative cash that first hit the industry in the late Aughts, while prestige TV was climbing the rungs of the culture, massive entertainment and media corporations had been swallowing what few smaller companies remained, and financial firms had been infiltrating the business, moving to reduce risk and maximize efficiency at all costs, exhausting writers in evermore unstable conditions.

“The industry is in a deep and existential crisis,” the head of a midsize studio told me in early August. We were in the lounge of the Soho House in West Hollywood. “It is probably the deepest and most existential crisis it’s ever been in. The writers are losing out. The middle layer of craftsmen are losing out. The top end of the talent are making more money than they ever have, but the nuts-and-bolts people who make the industry go round are losing out dramatically.”

Writers had been squeezed by the studios many times in the past, but never this far. And when the WGA went on strike last spring, they were historically unified: more guild members than ever before turned out for the vote to authorize, and 97.9 percent voted in favor. After five months, the writers were said to have won: they gained a new residuals model for streaming, new minimum lengths of employment for TV, and more guaranteed paid work on feature-film screenplays, among other protections.

But the business of Hollywood had undergone a foundational change. The new effective bosses of the industry—colossal conglomerates, asset-management companies, and private-equity firms—had not been simply pushing workers too hard and grabbing more than their fair share of the profits. They had been stripping value from the production system like copper pipes from a house—threatening the sustainability of the studios themselves. Today’s business side does not have a necessary vested interest in “the business”—in the health of what we think of as Hollywood, a place and system in which creativity is exchanged for capital. The union wins did not begin to address this fundamental problem.

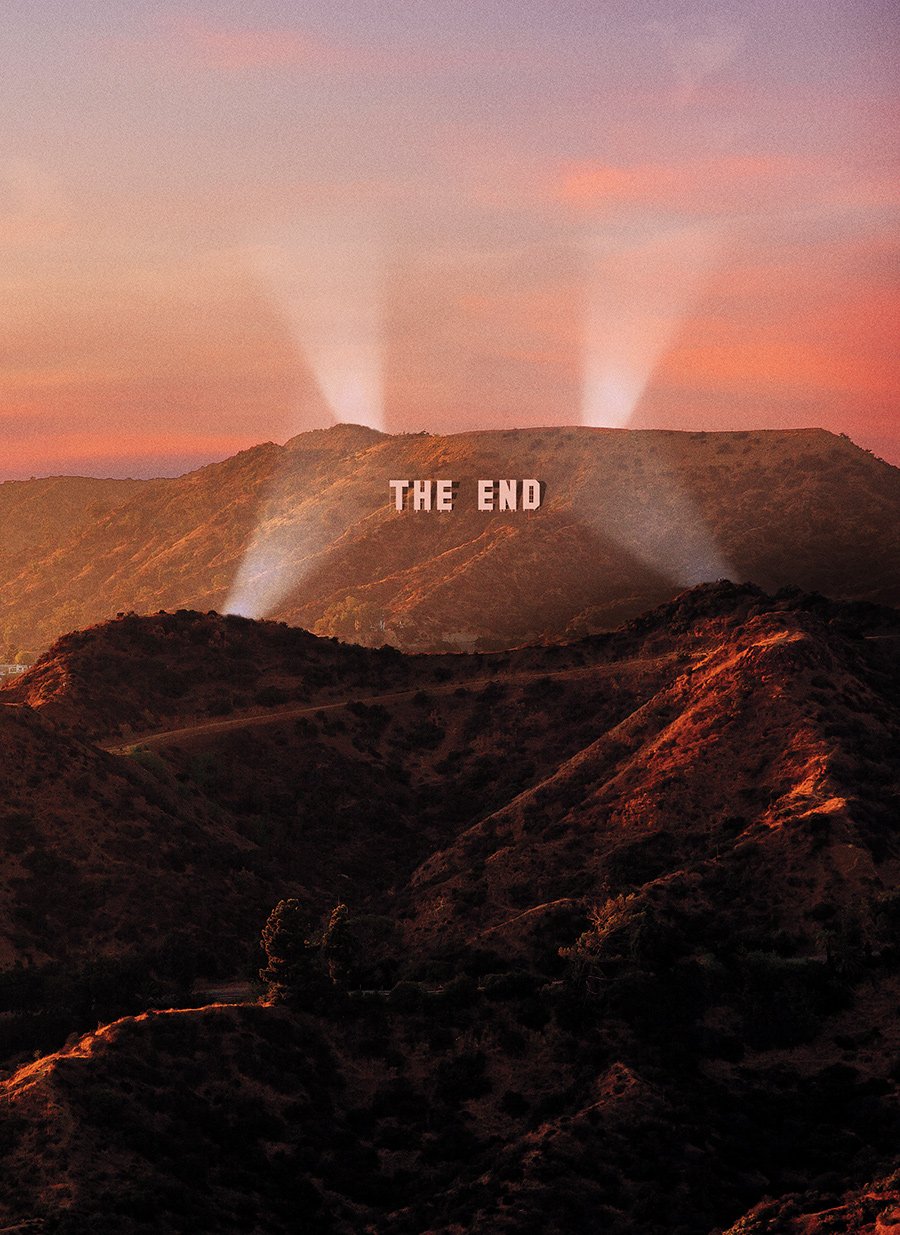

Profit will of course find a way; there will always be shit to watch. But without radical intervention, whether by the government or the workers, the industry will become unrecognizable. And the writing trade—the kind where one actually earns a living—will be obliterated.

To these speculators, Hollywood looked like a gold mine: the studios and entertainment corporations were ripe with redundancies and inefficiencies to be axed—costs to be cut, parts to be sold, profits to be diverted to shareholders, executives, and new, often unrelated ventures. And thanks to the deregulation of the preceding decades, the industry was wide open. Financial institutions could snatch up or take over large portions of companies in any area of the business; they could even acquire or substantially invest in groups in competition with one another—and they did, creating types of soft monopoly. Bets were even placed against the traditional industry as a whole, in the form of investments in Netflix, which promised to disrupt and dominate at-home viewing. Today the Big Three asset-management firms hold the largest stakes in most rival companies in media and entertainment.

The studios, now beholden to much larger companies and financial institutions, became subject to oversight focused on short-term horizons. This summer, I spoke with the head of a film and TV studio purchased by a private-equity firm in recent years. “It used to be there were these big, crusty, old legacy companies that had a longer-term view,” he said, “that could absorb losses, and could take risks. But now everything is driven by quarterly results. The only thing that matters is the next board meeting. You don’t make any decisions that have long-term benefits. You’re always just thinking about, ‘How do I meet my numbers?’ ” Efficiency and risk avoidance began to run the game.

Executives, meanwhile, increasingly believed that they’d found their best bet in “IP”: preexisting intellectual property—familiar stories, characters, and products—that could be milled for scripts. As an associate producer of a successful Aughts IP-driven franchise told me, IP is “sort of a hedge.” There’s some knowledge of the consumer’s interest, he said. “There’s a sort of dry run for the story.” Screenwriter Zack Stentz, who co-wrote the 2011 movies Thor and X-Men: First Class, told me, “It’s a way to take risk out of the equation as much as possible.”

The shift to IP further tipped the scales of power. Multiple writers I spoke with said that selecting preexisting characters and cinematic worlds gave executives a type of psychic edge, allowing them to claim a degree of creative credit. And as IP took over, the perceived authority of writers diminished. Julie Bush, a writer-producer for the Apple TV+ limited series Manhunt, told me, “Executives get to feel like the author of the work, even though they have a screenwriter, like me, basically create a story out of whole cloth.” At the same time, the biggest IP success story, the Marvel Cinematic Universe, by far the highest-earning franchise of all time, pioneered a production apparatus in which writers were often separated from the conception and creation of a movie’s overall story. “Working on these big franchises is a little bit like being a stonemason on a medieval cathedral,” Stentz told me. “I can point toward this little corner, or this arch, and say, That was me.” Within this system, writers have sometimes been withheld basic information, such as the arc of a project.

“When there’s high-profile IP involved,” Brancato told me, “writers tend to be treated as disposable.” “Everybody’s feeling fucked over,” he said. “The general sense is that you’re an absolutely fungible widget, and they don’t any longer take you seriously. It’s so broken. I mean, really, it is fucking broken.”

In the end, the precarity created by this new regime seems to have had a disastrous effect on efforts to diversify writers’ rooms. “There was this feeling,” the head of the midsize studio told me that day at Soho House, “during the last ten years or so, of, ‘Oh, we need to get more people of color in writers’ rooms.’ ” But what you get now, he said, is the black or Latino person who went to Harvard. “They’re getting the shot, but you don’t actually see a widening of the aperture to include people who grew up poor, maybe went to a state school or not even, and are just really talented. That has not happened at all.” To the extent that this was better than no change, he said, “Writers’ rooms are more diverse just in time for there not to be any writers’ rooms anymore.”

The supposed sure shot of IP is currently misfiring: in 2023, Disney’s The Marvels fell more than $64 million short of breaking even, and its Indiana Jones sequel drastically underperformed. The Flash, for Warner Bros. Discovery, lost millions, and the company’s Shazam! Fury of the Gods flopped. (In the case of Barbie—the loudest exception—the writers, Greta Gerwig and Noah Baumbach, were given extraordinary free rein.) As Zack Stentz put it, “Hollywood is based on giving audiences what they might not know. Any attempt to drive risk out of that process is sooner or later doomed to failure.” His words played off an old adage by the screenwriter William Goldman. “Nobody knows anything,” he wrote. “Not one person in the entire motion picture field knows for certain what’s going to work.” But investments in the alchemy of the creative process do not perform well in quarterly reports.

The film and TV industry is now controlled by only four major companies, and it is shot through with incentives to devalue the actual production of film and television. What is to be done? The most direct solution would be government intervention. If it wanted to, a presidential administration could enforce existing antitrust law, break up the conglomerates, and begin to pull entertainment companies loose from asset-management firms. It could regulate the use of financial tools, as deWaard has suggested; it could rein in private equity. The government could also increase competition directly by funding more public film and television. It could establish a universal basic income for artists and writers.

None of this is likely to happen. The entertainment and finance industries spend enormous sums lobbying both parties to maintain deregulation and prioritize the private sector. Writers will have to fight the studios again, but for more sweeping reforms. One change in particular has the potential to flip the power structure of the industry on its head: writers could demand to own complete copyright for the stories they create. They currently have something called “separated rights,” which allow a writer to use a script and its characters for limited purposes. But if they were to retain complete copyright, they would have vastly more leverage. Nearly every writer I spoke with seemed to believe that this would present a conflict with the way the union functions. This point is complicated and debatable, but Shawna Kidman and the legal expert Catherine Fisk—both preeminent scholars of copyright and media—told me that the greater challenge is Hollywood’s structure. The business is currently built around studio ownership. While Kidman found the idea of writer ownership infeasible, Fisk said it was possible, though it would be extremely difficult. Pushing for copyright would essentially mean going to war with the studios.

That's so sad. Alexa, play 1993 British dance-rock hit Open Up by Leftfield.