I'm talking about conventional perspectives on the lumpenproletariat; early marxists clearly ran in different circles than I do.

A contemporary definition from the Communist Party of Texas:

Generally unemployable people who make no positive contribution to an economy. Sometimes described as the bottom layer of a capitalist society. May include criminal and mentally unstable people. Some activists consider them "most radical" because they are "most exploited," but they are un-organizable and more likely to act as paid agents than to have any progressive role in class struggle.

I can just feel the classism dripping out.

The wikipedia article about the phrase basically illustrates the idea of the lumpenproletariat as having been used as a punching bag by Marx, to create a foil to the proletariat in order to glorify the latter's revolutionary potential. From The Communist Manifesto:

The lumpenproletariat is passive decaying matter of the lowest layers of the old society, is here and there thrust into the [progressive] movement by a proletarian revolution; [however,] in accordance with its whole way of life, it is more likely to sell out to reactionary intrigues.

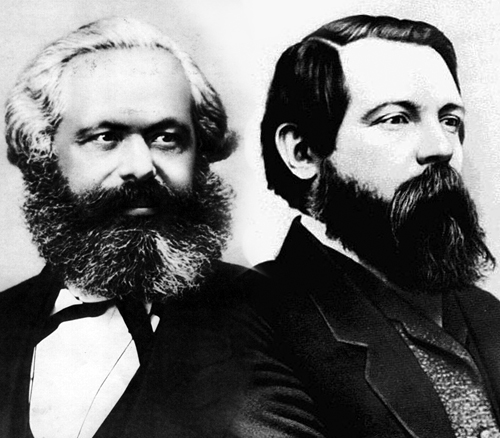

Anyway, I find this whole line of thinking precisely as deplorable as Marx, and Engels, and those who followed found the lumpenproletariat. Apparently Mao saw more revolutionary potential in the lumpenproletariat, believing they were at least educable.

It seems like the Black Panther Party looked toward the lumpenproletariat with some humanity, and they saw revolutionary potential in "the brother who's pimping, the brother who's hustling, the unemployed, the downtrodden, the brother who's robbing banks, who's not politically conscious," as Bobby Seale, in-part, defined the lumpenproletariat.

This feels much more honest and humane than the classical definitions, which I guess a lot of the major communist orgs in the u.s. still run with.

Finally, I'll just copy and paste the very short 'criticism' section from the wiki article as some food for thought:

Ernesto Laclau argued that Marx's dismissal of the lumpenproletariat showed the limitations of his theory of economic determinism and argued that the group and "its possible integration into the politics of populism as an 'absolute outside' that threatens the coherence of ideological identifications." Mark Cowling argues that the "concept is being used for its political impact rather than because it provides good explanations" and that its political impact is "pernicious" and an "obstacle to clear analysis." Laura Pulido argues that there is a diversity in the lumpen population, especially in terms of consciousness.

Anyway, just one of those 'holy shit' moments. Usually I vibe hard with classical marxism, but they can't all be hits. Wondering other peoples' takes.

But don't go telling me that my lumpen comrades are economically predestined to not be revolutionary socialists, because that analysis would run in direct contradiction to material realities ;)

I agree with this tho. It maybe be necessary to make a distinction inside the lumpen for modern conditions, such as it should be necessary to make a distinction inside the proletariat for modern conditions (lower class, middle class), stuff like petit burgeois. If we think of the lumpen as the pimps, the gangs, the mugger specifically the one who kills, they're basically anti-revolutionary classes, not inherently (you can have "gangs" like the Zapatistas, for example), but they tend to work in the capitalist framework, have no class consciousness, and have no desire to achieve class consciousness. Again, this is as a class, as a person you can try and turn everyone into a revolutionary. After all, the reason we have no revolution is because the great masses of the proletariat are not revolutionary, even though they are (and here we follow Marx) the revolutionary class by excellence. But if we follow Mao, the peasantry is the revolutionary class in China. For Lenin, it is the peasantry allied with the proletariat. We need to start re-thinking these labels, grasping class more intently when we study sociologically, making room for individuals, but overall just organise.