I'm talking about conventional perspectives on the lumpenproletariat; early marxists clearly ran in different circles than I do.

A contemporary definition from the Communist Party of Texas:

Generally unemployable people who make no positive contribution to an economy. Sometimes described as the bottom layer of a capitalist society. May include criminal and mentally unstable people. Some activists consider them "most radical" because they are "most exploited," but they are un-organizable and more likely to act as paid agents than to have any progressive role in class struggle.

I can just feel the classism dripping out.

The wikipedia article about the phrase basically illustrates the idea of the lumpenproletariat as having been used as a punching bag by Marx, to create a foil to the proletariat in order to glorify the latter's revolutionary potential. From The Communist Manifesto:

The lumpenproletariat is passive decaying matter of the lowest layers of the old society, is here and there thrust into the [progressive] movement by a proletarian revolution; [however,] in accordance with its whole way of life, it is more likely to sell out to reactionary intrigues.

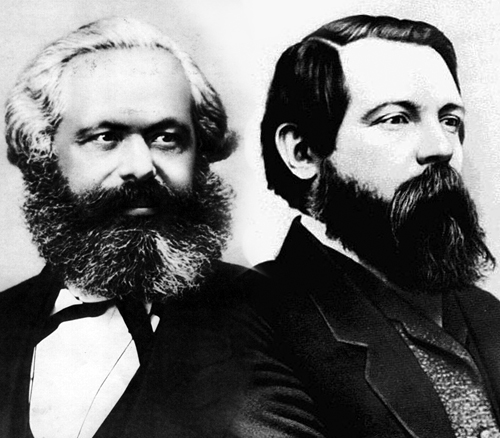

Anyway, I find this whole line of thinking precisely as deplorable as Marx, and Engels, and those who followed found the lumpenproletariat. Apparently Mao saw more revolutionary potential in the lumpenproletariat, believing they were at least educable.

It seems like the Black Panther Party looked toward the lumpenproletariat with some humanity, and they saw revolutionary potential in "the brother who's pimping, the brother who's hustling, the unemployed, the downtrodden, the brother who's robbing banks, who's not politically conscious," as Bobby Seale, in-part, defined the lumpenproletariat.

This feels much more honest and humane than the classical definitions, which I guess a lot of the major communist orgs in the u.s. still run with.

Finally, I'll just copy and paste the very short 'criticism' section from the wiki article as some food for thought:

Ernesto Laclau argued that Marx's dismissal of the lumpenproletariat showed the limitations of his theory of economic determinism and argued that the group and "its possible integration into the politics of populism as an 'absolute outside' that threatens the coherence of ideological identifications." Mark Cowling argues that the "concept is being used for its political impact rather than because it provides good explanations" and that its political impact is "pernicious" and an "obstacle to clear analysis." Laura Pulido argues that there is a diversity in the lumpen population, especially in terms of consciousness.

Anyway, just one of those 'holy shit' moments. Usually I vibe hard with classical marxism, but they can't all be hits. Wondering other peoples' takes.

But don't go telling me that my lumpen comrades are economically predestined to not be revolutionary socialists, because that analysis would run in direct contradiction to material realities ;)

Huh, the first thing I thought is that the three examples were already challenged in Engels' The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State almost 150 years ago, and as I understand it that book is considered mostly obsolete. I haven't studied anthropology 'seriously', but seeing the state of economics I'm not very surprised that people were still giving credence to the social contract and philosophy from the 1600s in 1970.

Thanks for the WEIRD paper, it seems very interesting.

Ya, I mean that was like some of the earliest anthropology. The data base they had was limited at the time—most of that book and theorizing at the time was based on interactions with the Haudenosaunee who, while amazing people, aren’t representative of humanity as a whole, like modern anthropologists try to examine.

Particularly, archaeology wasn’t very developed at the time; we now have a pretty precise timeline about the development of private property after the beginning of agriculture, as seen in the gradual privatization (and henceforth dis-equalization) of grain stores in the archaeological record. We also now know that we didn’t start off all matrilineal and then inevitably graduate to something else.

Probably a fourth really important development I should’ve mentioned, now that I’m thinking about marxism more specifically, is the ‘death’ of unilinear cultural evolutionism. This is the belief that all humans cultures start at A, move onto B, and are inevitably driven toward C.

This is found to be... not correct haha, and is pretty firmly baked into marxist thinking. It was baked into pretty much all thinking at the time, and still is. Whether you believe we’re destined for the stars, or for communism, or that capitalism is the end of history, or that any particular element of 'modern society' is simply better than all of what came before, a lot of people subscribe unknowingly to this anthropological assumption of inevitable directional progress which decidedly does not hold water, when you examine the evidence of anthropology.

And I really don’t fault Engels for thinking that way, nor do I discount his work because he was prone to those false assumptions.

One illustrative example: an Indigenous nation north of Lake Superior was one of the first cultures on earth to discover metallurgy, something like 5-10,000 years ago. They made copper knives for a few thousand years. But they didn’t just ‘move up the tech tree’ like we tend to assume. Nor did they run out of copper. They did decide, however, to stop making copper knives. No way to know why, but they moved ‘backwards’ or ‘down’ the tech tree, just because they did.

History, and contemporary society, is rife with such examples. So, contrary to popular belief, there isn’t some instrinsic forward/backward to humanity. It’s, fortunately, not so simple .