https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c0mzjm7knw7o.amp

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/11/19/russia-warns-ukraines-atacms-attacks-mark-new-phase-of-war

https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c0mzjm7knw7o.amp

https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/11/19/russia-warns-ukraines-atacms-attacks-mark-new-phase-of-war

![]() In his government?

In his government?

Surely Kamala will learn right? https://redlib.nohost.network/r/TrueAnon/comments/1g5zrmi/kamala_israel_has_a_right_to_defend_itself_and/?utm_source=share&utm_medium=mweb3x&utm_name=mweb3xcss&utm_term=1&utm_content=share_button

Hamas is decimated and its leadership is eliminated

LOL

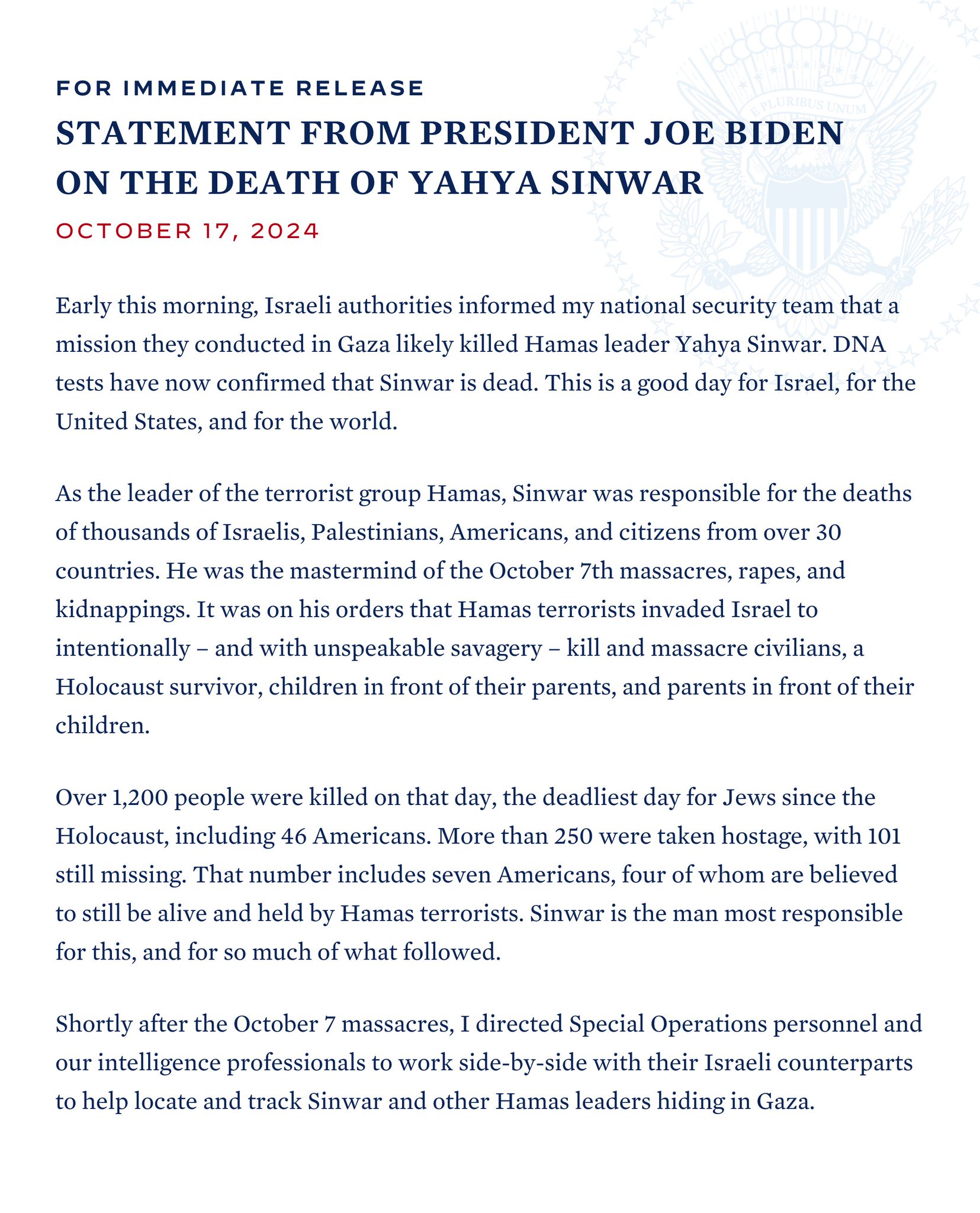

Biden:

Hamas leader Yahya Sinwar is dead.

This is a good day for Israel, for the United States, and for the world.

Here’s my full statement.

https://xcancel.com/POTUS/status/1846984629573542269

But ipecac doesn't make me ![]() , only reddit coal can

, only reddit coal can

[CW child abuse] Huw Edwards: Former BBC presenter given suspended sentence

over indecent images of children

this is the guy who announced the queens death

Huw Edwards has been spared jail for accessing indecent images of children as young as seven.

Prosecutor Ian Hope told the court Edwards had been assessed as posing a "medium risk of causing serious harm to children".

In sentencing remarks, district judge Paul Goldspring added he was at "considerable risk of harm from others" if he had ended up in prison.

random bullshit go defense incoming:

A separate report conducted by a psychosexual therapist said: "The feelings of being desirable and unseen alongside Mr Edwards's unresolved sexual orientation created a perfect storm where he engaged in sexual infidelities and became vulnerable to people blackmailing him."

The judge also said that Edwards was of "previous good character" and, until now, had been "very highly regarded by the public" - whom to many he had broken the news of the late Queen's death.

[...]This created an "enduring cognitive dissonance and low self-esteem", which was "compounded by a sense of being inferior" by not getting into Oxford University and going to Cardiff instead and "being therefore something of an outsider at the BBC".

0 time in prison. Another ![]() banger

https://www.google.com/news.sky.com/story/huw-edwards-what-was-his-defence-after-disgraced-veteran-bbc-presenter-avoids-jail-13216325

https://news.sky.com/story/amp/huw-edwards-former-bbc-presenter-given-suspended-sentence-over-indecent-images-of-children-13214373

banger

https://www.google.com/news.sky.com/story/huw-edwards-what-was-his-defence-after-disgraced-veteran-bbc-presenter-avoids-jail-13216325

https://news.sky.com/story/amp/huw-edwards-former-bbc-presenter-given-suspended-sentence-over-indecent-images-of-children-13214373

completely unrelated:

Five Just Stop Oil activists receive record sentences for planning to block M25

https://www.google.com/theguardian.com/environment/article/2024/jul/18/five-just-stop-oil-supporters-jailed-over-protest-that-blocked-m25

Unfortunately the terrorism situation looks incredibly bad (France was already useless at tackling it though)

They're trying to mock this person https://xcancel.com/ijzimx/status/1833794778871271779

The quotes are awful

21% of reform is even more insane, we could form a British ACP to split their vote ![]()

C2DE isn't a party, it's just a social classification

Worryingly, young people in the U.K. (ages 18-34) also have the highest levels of support for communism (29 per cent) and fascism (19 per cent) among the four countries.

yeah those are both equally worrying!

deleted by creator

My mum is catholic and she does sometimes.. she's ambivalent to this pope but she LOVED pope John Paul II (the one that almost got assassinated, not the one who probably got murdered)

https://xcancel.com/RnaudBertrand/status/1835171408256942149

Pope Francis: "China is a country with a capacity for dialogue and understanding that goes beyond other systems of democracy."

I agree, this video made me sick [CW sadistic treatment of migrants by Saudi border patrol] https://youtu.be/RsLwaauLCfo, they will definitely do this in the west when the crisis gets worse.

And I didn't have a solution but you're right, the western elites caused this, if they didn't want violent resistance then they shouldn't have ruined our planet. They should never know peace for what they've allowed to happen.

https://xcancel.com/pawelwargan/status/1834901542782021887

Harris is positioning herself as a Reaganite warlord in a chilling ad that makes clear as day that the Cold War—which proved unbearably hot for the tens of millions of lives the US destroyed in the Third World—was and will continue to be the consensus project of US imperialism.

LMAO - "[Reagan] 'Mr Gorbachev, tear down this wall,'

[JFK] 'And when one man is enslaved, all are not free,'

American presidents, Republican and Democrat, have always defied Russia's communist dictators, and defended American ideals.

Kamala Harris gets this. [Kamala] 'If we stand by, while an aggressor invades its neighbour with impunity, they will keep going,'

Kamala Harris will stand up to Putin, protect our allies, and keep us safe."

It feels like if France had a colony in eastern europe

Do you have any resources to read about climate change? I know that things will get worse but I'm pretty illiterate on the specifics

They turned it into the Trafford Centre