This small essay by Janine Brodie called "Power and Politics" has several other issues, but their most frustrating one is their outright DISMISSAL of Marxist class analysis for the stupidest reasons. Economic determinism? I guess if you yearned to softly dismiss marx by misrepresenting him.

God I fucking hate poli sci majors.

The previous page:

The next one:

I'm not the brightest crayon in the box but is it just me or does Doctor Brodie somehow make politics and power some sort of vague, unsolvable mystery? Like fr I don't want just an echochamber of nodding heads plz help am I in the wrong?

I need help putting words to my issues with it.

Weber's work, thus, encouraged social scientists to talk about class divisions in non-antagonistic ways. Social class was analyzed along a continuum - upper class, middle class, and lower class - without any notion of exploitation or conflict among these groups.

God this pisses me off so much. Its been a while since I've studied Weber, so I don't remember if this is an accurate representation of his views, but this notion just fucking sucks.

Basically, she presents class as something that is not real. Class, when reduced to "upper, middle and lower" under capitalism, is an entirely aesthetic definition. Under feudalism, upper, middle and lower were real classes, wherein the upper class were those who owned land, the main form of wealth and representation of production, the middle class neither owned nor worked the land, but were free, and often educated and literate (guilds men, bureaucrats etc) and the lower class, who worked the land and were not free (peasants, slaves, serfs). This is a real distinction defined by the relationship of people to ownership of land.

But under capitalism, these terms are completely meaningless in terms of telling us what someone does for a living. A capitalist and a famous athlete, for example, are both upper class, despite one working for their wages and the other exploiting the labour of others. A doctor might be middle class, but they might also be upper class depending on how rich they are. A lot of people won't even say the words "lower class" or "poor", instead saying "working class", completely bastardizing the term as an innuendo for poor, because they feel uncomfortable acknowledging that there are poor people.

So what makes one upper, middle, or lower class under capitalism? Whatever you think. Most people want to think they're middle class, especially those who make significantly more than the average person (ie, people who make 100,000+ a year but are embarrassed to call themselves rich). Being middle class is about taking two vacations a year abroad, or having a laundry room, or having two cars and 2.2 children, or eating a fancy meal twice a month. Feeling middle class is being middle class. Being lower class is living in a "working class area", not being able to afford a good house, struggling to pay bills. More material than middle class, but still nothing of value. Being upper class is anything between a proletarian making 80,000 dollars a a year in their tech job, and Elon Musk. The divisions are undefined and ever changing - the difference in upper, middle and lower class is only ever a cultural attitude.

So when Bodie says that Weber encouraged social scientists to examine society on a basis of upper, middle and lower class, you should disregard the word "scientist" from their job title, because there is nothing scientific about this approach. They analyse vibes and prestige aesthetic, which can never be proven or disproven, therefore it is impossible to say that they are definitively wrong. Nothing about the upper-middle-lower class model is based in material, provable, measurable reality, which is the realm where science tends to take place.

This is not a social science at all; it is pure idealism

without any notion of exploitation or conflict among these groups.

Might as well try and analyze a clock without any notion of friction between the gears

I think there could be sociological analysis of what the idealistic visions of class say about how a culture sees itself. But it couldn’t be an analysis of the social structure itself, just an analysis of the narrative.

For liberals, the "problem" with marxism is that Marxism ignores the superstructure of society and only looks at the base. They will then point to the existence and influence of the superstructure as a refutation of Marxism.

I have literally never seen a liberal ever even comprehend the idea that the superstructure of a society is shaped by its base. That is what Marxism actually is. Do they think Marx did not understand gender, racial or religious discrimination? Or course he did. He talks at lenght about these things.

Some of Marx and Engel's most famous texts, like "the origin of private property, the state and family", for example, studies the emergence of the patriarchy.

But he does so from a material standpoint. That is what grounds his analysis at every point.

We must understand that the value of the Marxist philosophical project is that it is never content to simply accept the existence of things as they are by relying on notions of some "human nature", "god", or any such ideological nonsense.

It is similar to how you cannot truly understand how computers work, in all of their intricacies, without understanding how a transistor works. Liberals are people who refuse to acknowledge the transistor. For them, their computer is the magic box which dispenses treats.

As a poli sci major, there are two broad camps of people in the field, when it comes to Marxism.

First are the people who do shit you're complaining about, where they "refute" Marxism without understanding a Damn thing about it.

And then there are the people actually doing Marxist analysis. The people actually doing Marxist analysis are mostly comparativists in the subfield of political-economy (Yes, it still exists, just as a sub-field of a sub-field of poli sci).

And the way these groups interact is the first group nods their heads in agreement with the Marxists. But only so long as it's called "political economy" and not Marxism. The minute you call it Marxism, they start trying to tear it down, even when they were just agreeing with it, five minutes ago.

Sounds just like when liberals will agree with communism as long as you don't call it communism.

It's always the exact same middle-school reading of Marxism, holy shit. Somehow none of these experts figures there's something wrong with comparing an inflammatory political pamphlet for a party and a fully fleshed out technical publishing.

I wonder why these geniuses never criticize the actual technical works Marx did 🤔 it's ALWAYS just the manifesto for a party, and that's it.

Anyway, a rule of thumb: this person doesn't take their own work seriously, so I'm not gonna take their work seriously either.

Not only is the manifesto the only work they touch on: they only mention history being class struggle and more people being pushed to either bourgeois or proletarian. While it's been awhile since I've read the manifesto, I'm pretty sure that even in that pamphlet Marx briefly goes into how and why that is the case. It's like this Brodie person didn't even read beyond the first 3 pages.

Oh Christ. JANINE FUCKING BRODIE?

I have personal beef with this woman. She's one of those liberals that will repulse you from becoming a liberal, purely based on how up their own ass they are.

e: corrected her professional name

THE SMUGNESS RADIATES FROM THE FUCKING SCREEN

My issue with figures like Weber and Foucault and Bourdieu is that, to varying degrees, they don't just obfuscate class analysis but they actively mystify it by turning it into something abstract.

One of the greatest ways that people, whether big figures in academia or the media or just laypeople, strawman Marx is by beginning from the presumption that Marx sought to detail every little thing in political economy and then they proceed to do things like going "Aha! Marx was a fool for he did not account for the individual who draws exactly half of their income by being employed and the other half from owning some sidehustle business. He doesn't even have a name for a person who straddles his so-called classes. Ridiculous!" or "Aha! Marx failed to account for the fact that power exists outside of people's relationship to the means of production. How shortsighted of him!"

But the thing is that Marx took a systemic analysis. He wasn't trying to create special little titles for each minor graduation between proletariat and petit-bourgeoisie/bourgeoisie. He wasn't particularly concerned with how an individual might straddle these categories because ultimately it doesn't bear much relevance to his analysis whatsoever. Likewise he didn't go into great detail about gender relations under capitalism because he was occupied with the system itself and in writing volumes of Capital.

I don't think that Marx ever argued that his analysis of capitalism was the Theory of Relativity for political economy. When it comes to sociological matters there's always going to be edge cases and odd little intricacies that cannot be accounted for in the way that a hard science can (mostly) do. That's because people are complex and societies are astoundingly elaborate. There's plenty that can be gained from understanding things outside of what Marx wrote and even from looking beyond Marx's model, sure, but at the end of the day class conflict is the engine of society and it determines how we structure our lives and our world.

Marx and Engels did concern themselves with gender relations under capitalism, in fact they wrote about it at length.

Sure but tbh they didn't go into it in great detail as they did with capitalism or to the extent that later gender theorists did.

I guess? Gender relationships crop up all through Marx and Engels work, in many cases, substantial time is taken to understand the nature of these relations. Marx doesn't go into gender theory because gender theory wasn't really even a thing at the time, and wouldn't be until developed later by students of Marxist social theory, though then thrown to the cobbles by Stalin (one of his real big fuck-ups).

stalin did not throw gender to 'the cobbles'. Inflammatory language aside, He was mostly concerned with the National Question and Soviet Economic development.

https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/stalin/works/subject/women/cccp.htm

https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/stalin/works/subject/women/jauccf.htm

His referenced works in the marxists internet archive do not seem to whitewash the role of women in the revolution. If that isn't enough, Women in the USSR under his tenure also experienced massive economic and political emancipation.

Lenin liberated women, stalin followed. there were some reactionary steps back, but such is usually true in all socialist countries in order to maintain stability and popularity.

i have been graced with a ReadFanon post

thank you very much, this put it into very good words my issue of just dismissing marxist class analysis based on a dogmatic reading of him.

Real "If you ignore all the things that cause the gender pay gap, the gender pay gap goes away" energy.

Marx was not intersectional as we would call it today because he existed before 3rd. Wave Feminism. However, he absolutely included things like oh, I don't know....literal fucking slaves? as part of the proletariat.

We're gonna need a bigger re-education camp.

Edit: okay I was being facetious but I'll serious post. No, slaves aren't technically proles. I was just going in a blind rage over this person essentially calling Marx "class reductionist" (without using that term because it's a communist one) when the dude was literally an abolitionist at a time where chattel slavery wasn't seen as morally abhorrent.

It's such a bad-faith interpretation I can only assume the author and the prof who recommended them are deeply unserious people. They are classist, asshole, professional managerial personnel. It's like "I'm speaking" manifested into a peer-reviewed study from pseudo-intellectual academic snobs with degrees from the reputable school of wherever the fuck.

Marx did not include slaves as part of the proletariat. Not that they weren't a class that did not deserve and should fight for emancipation, but that they did not have the means and knowledge to recreate society in such a way that could de-fetishize and out-compete industrial capitalism. Marx believed that slave-based production was incredibly economically inefficient compared to capitalism and would die either a natural or artificial death, and be replaced by the proletariat and peasent class. Of which he was partially right, though slavery has never really gone away it is no longer the base of production for any society (though it is the base of infrastructural development in most of the Gulf States).

it is very important to make a distinction between classes of different modes of production

However, he absolutely included things like oh, I don't know....literal fucking slaves? as part of the proletariat.

Did he? Proletariat and slave are very different economic positions. They're explicitly contrasted in The Principles of Communism section 7: "In what way do proletarians differ from slaves?".

I don't have a good citation at hand but Marx also distinguished between peasants and proletarians, the former being agrarian and the latter industrial workers.

Could one be both proletarian and slave? Depends on how you'd define slave and prole, I imagine many sorts of live in house help in cities might qualify.

Idk what Marx said about it

It's been awhile, but If I remember correctly, proles have to be free citizens, because they have to be free to move to where work is. While you could theoretically have a slave that you contract out to industries, the fact that you have to make a contract with an owner means you bear a fiduciary duty to that person that you (at the time of writing) did not owe to a prole. However, contracting slave labor for factory work did not fit the model of slave-based production at the time (the Southern U.S. being the model Marx would be discussing).

Now that doesn't mean that most proles aren't engaged in wage slavery, but that is a fundamentally different animal than legal slavery, as the slave is not a legal 'person' but instead a literal commodity, the slave being the commodity rather than strictly the labor the slave provides.

Personally I don't really think so. A slave is property, can be bought and sold, doesn't have the freedom to attempt to find work elsewhere.

Ah, so it would just be a slave doing city things, going and getting groceries etc but avoiding that specific part of proletarianisation

Yeah, there were many urban slaves in the northern colonies/states in early America, for example, and they also did housework, waiting on their owners, childcare, and things like that.

I lost the thread on this conversation with my earlier reply. Yes, there were many urban slaves, no, they weren't proles. Proles work for wages (or commission or salary) which they use to buy their means of subsistence; slaves work for free and are given means of subsistence (most of the time) simply so they can keep performing their duties.

I think both are the products of vastly different demographic and productive contexts. The slave is economically viable when the difference between the average productivity of labor(which is the value produced by labor) and the marginal productivity of labor(which liberal economists consider equal to the wage, they are wrong but for simplicity let's say they are close enough) is very low. This forces the overlord to apply maximum coercion in order to extract surplus. But coercion is expensive, so as the gap between these 2 quantities grows naked coercion is relaxed. Until you get to a "free market". But even the reserve army of labor is a form of coercion since it serves too keep wages under the mpl.

So from an economic perspective being a slave and a proletariat are at opposite ends of economic conditions.

Note that this gap is defined by the productive technology but it does not necessarily mean that the gap grows as society advances technologically.

Also note that this also applies to high value slaves like the ones in the medieval Islamic societies, that were generals, scribes and administrators.

I was thinking more a live in house-worker in a wealthy household (but in an otherwise poor city) who gets room and board but also has their passport taken and the authorities go looking for them if they are missing for a day, but also sometimes they do the groceries and get access to dad's credit card to facilitate such ends, but doesn't really have the capacity to own property, vote, participate in society etc etc. They certainly participate in some proletarian activities and relationships, but also some slave-y ones.

Not saying that this would be the majority of people in any economy, just exploring if its possible to be both Proletarian and a Slave. Someone else in this thread says that an important part of being a prole is being able to move to where the jobs are and choose which jobs they do (on some level; its never that clear cut).

I get what you mean. As other people in the tread have said, the relationship between a proletarian and production is wage labor. Mobility is indeed an important part of that, as well as being a nominally free individual. So it's not so much what job they are doing, or their other social relationships.

But these liminal examples do rise the concern that our definitions can be too rigid.

I thought of 2 other related points between my last post and this one. The first is about tenancy. As the marginal productivity of agricultural workers falls, the become landless, and eventually end up working the land for a fee or corvee. The same conditions that correlate with tenancy also do so with proletarisation, the difference in outcomes for different regions seems to be related to mobility, and the development of nearby urban networks.

The second was about eastern European serfs, who had become tenants, tied to the land and owed the landlord a corvee. But as agricultural productivity fell with respect to labor productivity on urban areas, landlords decided it was more profitable to let the serfs work in the city and then pay them a fee. So these people belonged to 2 different contexts, on the one hand their relationship to production was that of proletarians, on the other they were also explored by the landlord who had customary rights over them.

This is another example of how definitions can become too rigid, and can't represent Al the nuances of the real world. At the same time clear definitions help us understand the difference in this case between the material and customary relationships. In this example the landlords went to the dustbin of history because they no longer had an economic base.

Engels has written this about slaves/proles, can't right now remember exactly where it is from, but happened to have it handy:

In what way do proletarians differ from slaves? The slave is sold once and for all; the proletarian must sell himself daily and hourly.

The individual slave, property of one master, is assured an existence, however miserable it may be, because of the master’s interest. The individual proletarian, property as it were of the entire bourgeois class which buys his labor only when someone has need of it, has no secure existence. This existence is assured only to the class as a whole.

The slave is outside competition; the proletarian is in it and experiences all its vagaries.

The slave counts as a thing, not as a member of society. Thus, the slave can have a better existence than the proletarian, while the proletarian belongs to a higher stage of social development and, himself, stands on a higher social level than the slave.

The slave frees himself when, of all the relations of private property, he abolishes only the relation of slavery and thereby becomes a proletarian; the proletarian can free himself only by abolishing private property in general.

What Marx said about it (emphasis added)

Aristotle therefore, himself, tells us what barred the way to his further analysis; it was the absence of any concept of value. What is that equal something, that common substance, which admits of the value of the beds being expressed by a house? Such a thing, in truth, cannot exist, says Aristotle. And why not? Compared with the beds, the house does represent something equal to them, in so far as it represents what is really equal, both in the beds and the house. And that is – human labour.

There was, however, an important fact which prevented Aristotle from seeing that, to attribute value to commodities, is merely a mode of expressing all labour as equal human labour, and consequently as labour of equal quality. Greek society was founded upon slavery, and had, therefore, for its natural basis, the inequality of men and of their labour powers. The secret of the expression of value, namely, that all kinds of labour are equal and equivalent, because, and so far as they are human labour in general, cannot be deciphered, until the notion of human equality has already acquired the fixity of a popular prejudice. This, however, is possible only in a society in which the great mass of the produce of labour takes the form of commodities, in which, consequently, the dominant relation between man and man, is that of owners of commodities. The brilliancy of Aristotle’s genius is shown by this alone, that he discovered, in the expression of the value of commodities, a relation of equality. The peculiar conditions of the society in which he lived, alone prevented him from discovering what, “in truth,” was at the bottom of this equality.

There's an article on Marx and Engels views on women's rights here but there's this quote from Engels if you don't read the article

The first class opposition that appears in history coincides with the development of the antagonism between man and woman in monogamous marriage, and the first class oppression coincides with that of the female sex by the male

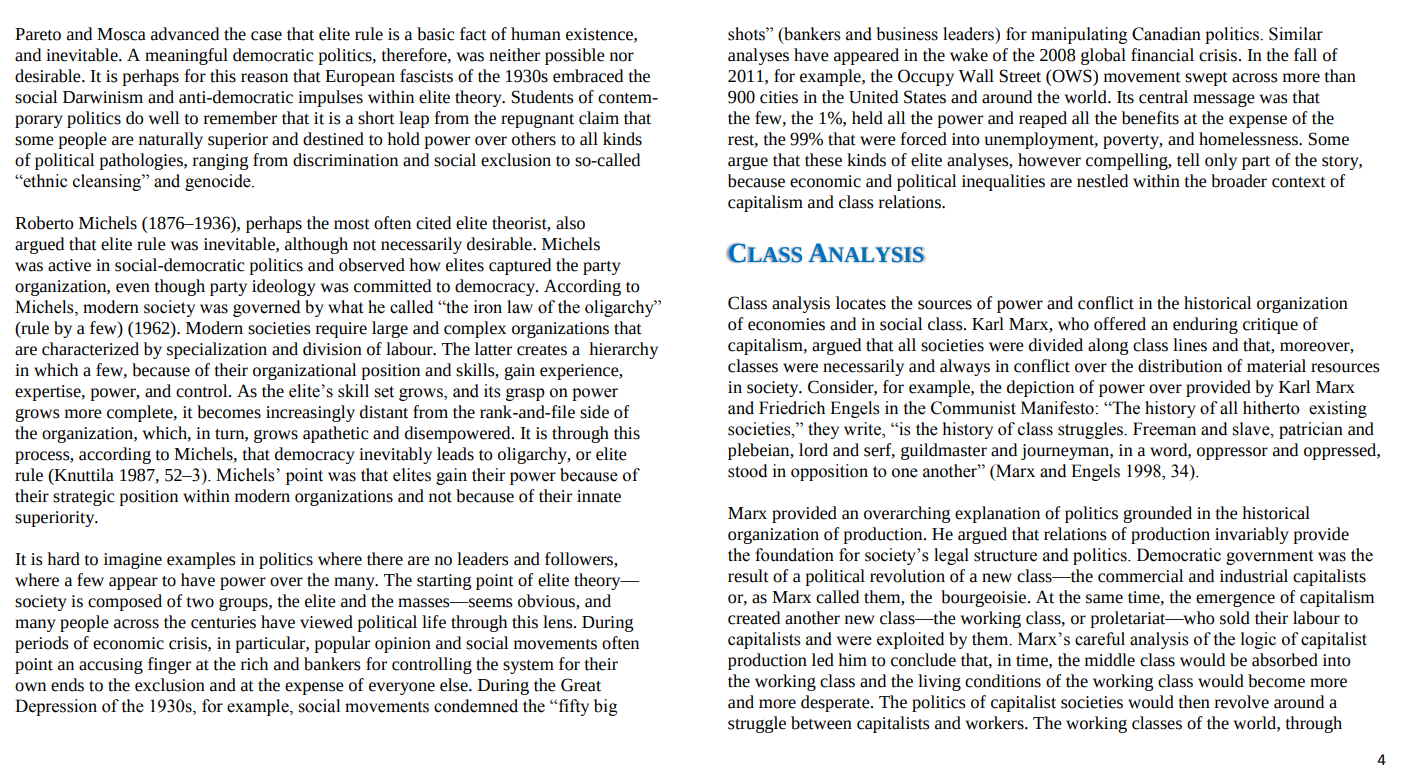

The author portrays an evolution of social and economic theory that passes from Marx to Weber to Foucault. In other words, Marx without Lenin. The tactic is diversionary rather than disinformative. Insofar as you will discuss Marxism, it will be in the context of critiques of Marx made by academics operating in capitalist countries. I don't mean to say that Weber's or Foucault's theories are entirely wrong headed, just that as long as you are occupied with them you will be ignoring the strains of Marxist theory that have underpinned any actually successful Marxist political project.

If you want to pick nits though, this passage made me squint:

Democratic government was the result of a political revolution of a new class-the commercial and industrial capitalists or, as Marx called them, the bourgeoisie.

Here the author is stating without citation that Marx believed democracy was achieved by bourgeois revolution. Big if true. Perhaps a certain kind of democracy within a certain class? Where did Marx make this claim?

That quote also telescopes hundreds of years of development through a bourgeois lens, no less. One only need read the three paragraphs in the Manifesto before M&E say that capitalism has simplified classes to see the echo of a subtler conception of class than is presented in Brodie's work. That is, even Brodie's limited actual engagement seems to take ideas/quotes out of context and uses them as gotchas.

I wouldn't say the quote necessarily attributes to Marx the belief that 'democracy was achieved by bourgeois revolution'. There's a way of reading that claim as Brodie's garbled understanding of bourgeois revolution followed by a claim about Marx's class analysis. But here we see an alternative problem beneath the text.

If we read Brodie instead as saying that Marx only called the 'new class—the commercial and industrial capitalists … the bourgeoisie', the question is, does Brodie agree? Is Brodie sceptical that a bourgeois class exists at all? Is the bourgeoisie only the bourgeoisie according to Marx?

It wouldn't be the first time a bourgeois writer has rejected the notion of a bourgeois revolution (the underlying topic, here). But that rejection usually starts by claiming that humans have always lived under or driven (teleologically) towards capitalism; i.e. there is no 'new' class of bourgeois because the bourgeois always existed (just don't look too closely at feudal lords, etc). It doesn't usually reject the existence of a bourgeoisie, although that term is usually replaced with the friendlier-because-more-obscure 'capitalists'.

That's a problem with the writing, rather than your interpretation. It's making me squint, too, and it's hard to know who is supposed to be saying what without any real engagement with what Marx (or specific Marxists) have said.

Fair enough if Brodie has unknowingly read a summary of a summary of e.g. GA Cohen but that needs to be made clear. The problem is that academics can write shit like this but they must uphold the pretense that it's rigorous. So they can't start admitting what or who they have actually read or to what extent.

for some reason it won't let me post more than 6 photos, which is weird. I'll try sending them in the morning

i can link the full 9 pages for you, here

part 1

spoiler

___

Show Show

Show Show

Show Show

Show Show

Show Show

Show

Thanks for this, I'll read through it later.

In the meantime, I've had a quick look at the author. What I will say is that successful career academics like Brodie are good for one thing in particular: they tend to represent the orthodox state of affairs even if they create their own brand around the edges. This means you can read a few of their articles, maybe a book (skimming the waffle sections) for a snapshot of the mainstream, 'critical' but uncontentious thought.

When you write for an academic audience that has been trained to think in a certain way, you're at disadvantage as a Marxist. You know they'll reject you if you push the Marxism too fast or too hard before you have demonstrated your intellectual credentials.

Opening an essay with close, analytical, and critical engagement with writers like Brodie let's you show your reader (examiner) that you know what you're supposed to know. This can also help to lure the reader in to accept your challenges, left with the question, 'okay, so now what?'

And that's when you can hit them with the Marxism, with or without directly referencing (well known) Marxists (including Marx). For example, you can present evidence of what's been said elsewhere in this thread about the uselessness of lower, middle, upper class by asking what's similar about an senior engineer at Tesla ('upper class') and the owner, Musk. This lets you question the orthodoxy in a way that leads back to Marxism without letting the reader know until it's too late for them to reject your argument on it's face for being Marxist.

This approach doesn't always work and it's not a fixed blueprint (a lot also depends on the learning outcomes and the marking criteria, etc) but maybe it'll help you power through when you're given other anti-Marxist readings.

Tagging @SpaceDogs@lemmygrad.ml as you might be interested in this thread if you haven't seen it.

Me thinks Janine Brodie has only read the Communist Manifesto…

I don’t really have an excuse as to why it took me so long to read this thread, but I finally did and I wanted to thank you for tagging me. Your comment (and all your comments) is very useful for me as a student and future professor, especially that bit about being a Marxist in academia. If the paper is not about Marx directly I really do have to censor myself quite a bit by talking about Marxist ideas and views but not referencing Marxists themselves for fear of being penalized.

To me, this piece by Brodie comes across as Political Science 101. It’s incredibly status quo and doesn't say much of anything outside of what is already well established. I’m not going to speculate what year OP is in, but this is not out of the realm of first year PoliSci. While I don’t recall ever reading anything by Brodie in any of my classes, I’ve read and been lectured to in the same language. She is also a Canadian academic so maybe thats also why I am sensing severe overlap.

Glad you found the discussion helpful.

I realise this was a month ago now. Can't believe I've not posted for that long!

I agree with everything @wrecker_vs_dracula@hexbear.net said. However, I also want to add this.

Social theory is more fun for academics than economic theory, but economic theory is actually where most social theory stems from. Even Foucaoult and Weber do not discount the real affect of the material base on the superstructure, but rather attempt to document the changes and reactions within the superstructure, that in turn partially influence the base, but are not driven by it. That being said, the more esoteric, and narrative-driven the claim, the more likely you will be cited and used in undergrad classes (like this particulsr essay!). Nobody wants to be the professor that assigns pricing tables and labor value calculations to the poly-sci students. They'll just cheat anyways.

It is also very clear that the good doctor is engaging in an Western academics conception of Marx, maybe having read one or two books by Marx, maybe a book by Engels, and maybe a compilation by another Western academic or sociologist who specializes in Weber, or maybe even Weber himself. But it is pretty clear she is on the whole unfamiliar with what Marx actually said about things, as Marx himself was not a vulgar materialist or even a materialist determinist, but rather felt that all good political economic analysis has to start at the base, and can only proceed from there, as the economic base is the primary driver that either rewards or punishes individual or cultural ideological shifts.

After-all Marx advocated struggling against the current form of production to create a new one, he clearly believed in the ability for the base to be altered by the superstructure, just that the base has to exist to reward the new superstructure that comes into being or else it will wither and die. You can't just start a utopian commune in capitalism and expect it to remain unaltered by the capitalist mode of production, which will inevitably alter the superstructure to something that can be used by capitalism.

A search for the essay online shows that it's meant to be an introductory social science text for undergrads. This explains why it's not written with the expectation that it will have to present arguments. It's good enough for Brodie to say "such and such writer was very important, but another writer disagrees." It doesn't do the work of properly explicating theoretical disagreements between thinkers, because that's not the goal.

Your professor is gripped by what Friere called the "banking model" of education, wherein the job of the teacher is to simply deposit information into students so it can be retrieved later. I think you're fine to just tell them "I am aware of the existence of Weber. He's wrong."

The starkly oppressive conditions of the emerging industrialization had been somewhat improved,

THEY SAID THE LINE!!!

broader historical contexts of racism, sexism, homophobia, and colonialism

later thinkers expanded on Marx's original ideas to include intersectional critiques, read Settlers etc. etc.

Prestige could involve things as intangible as tastes and patterns of consumption that are socially valued, such as driving a Mercedes or being a celebrated athlete, a hip-hop artist, or a movie star. This kind of social power, while not entirely unrelated to social class, is not reducible to economic relations alone.

"Prestige could also involve things as intangible as... driving an expensive car or being a multimillionaire, things that can be seen as distinct enough from any economic relations such that I can use this as proof that gommunism stoopid."

Cope-ine Brosciencedie is reaching new heights of mental gymnastics.

Yeah there’s a certain similarity there with creationists who argue “oh Darwin didn’t get this one bit right or didn’t account for some factor, ergo evolution is wrong.” Factoring social characteristics into class analysis doesn’t render the class elements irrelevant.

I can never remember the source of the quote but I once read something to the effect of: "It is a testament to the insidiousness of capitalism that it has convinced a majority of Americans that the American system of chattel slavery was historically a simple series of race relations that had absolutely nothing to do with the production of cotton and sugar."

These things often are not mutually exclusive concepts in practice.

I always have to point out to them, when was the last time a celebrity made a systemic change that actually lived past their death? Can you think of a single one? How has pro athletes giving turkeys out to poor neighborhoods on Thanksgiving alleviated poverty? Remember what happened to Colin Kaepernick when he presented a very mild critique of the power structure? It's almost as if any amount of social status that is not organized within the working class is doomed to be an ephemeral moment in time, because it cannot be protected and safe guarded by labor.

I need help putting words to my issues with it.

I read the first screenshot and was going to ask: how do you deal with nonsense like this? Looking forward to hear other people's answers.

I just can't get my head around where to start with rubbish like this. How do you even broach the subject when the subject is: 'you published an academic article criticising Marxism on the basis of whatever you thought it was in a dream because you clearly haven't read any Marx except maybe you misunderstood the Manifesto on the bus to college as a hungover undergrad because the editors and reviewers were equally illeducated; luckily for you, you are repeating the same thing that everyone else who hasn't read Marx also believes so you are likely in for a lucrative career'.

How do you even broach the subject

Probably with a copy of Kapital opened to page one, Malcolm X speeches playing in the background, and a gun at the back of their head while they read the whole thing outloud to the rest of the class.

I'm not the brightest crayon in the box but is it just me or does Doctor Brodie somehow make politics and power some sort of vague, unsolvable mystery?

This is typical of a lot of liberal analysis. There aren't any conclusions to be drawn, just devastating questions to ponder, and by reading about & pondering them without getting anywhere you are a good little intellectual deserving of treats. Every article I see about corporate malfeasance in The Atlantic or NYT has this exact same goes-nowhere style.

Ok, so on one hand you have Marx's analysis of class, and on the other hand you have a more granular examination of power from Foucault. These don't seem like they're mutually exclusive, just examinations at different two very different scales. But the way how it's written it almost comes across like the author thinks they are? I don't know Foucault at all, though; im only going off of how he's being summarized here.

Calling Marx an economic determinist is like calling Newton a physics extremist: he just called it as he saw it, man.