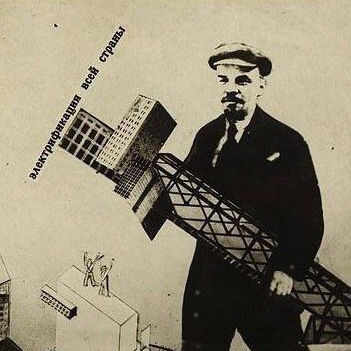

Welcome to baby Marxist rehabilitation camp.

We are reading Volumes 1, 2, and 3 in one year. (Volume IV, often published under the title Theories of Surplus Value, will not be included in this particular reading club, but comrades are encouraged to do other solo and collaborative reading.) This bookclub will repeat yearly until communism is achieved.

The three volumes in a year works out to about 6½ pages a day for a year, 46⅔ pages a week.

I'll post the readings at the start of each week and @mention anybody interested. Let me know if you want to be added or removed.

We currently have 58 members!!! I expect a certain drop-off rate, but I'll be thrilled if a dozen or couple dozen read it.

If you've made it this far, you've already read ¹⁄₁₈ of Volume I. The first three weeks are the hardest, after that it'll be quite easy, and only requires 20 minutes a day (endurance is key).

Just joining us? It'll take you about 2-3 hours to catch up to where the group is. You can do that on one long bus ride.

Archives: Week 1

Week 2, Jan 8-14, we are reading Volume 1, Chapter 2 'The Process of Exchange', PLUS Volume 1, Chapter 3, Section 1 'The Measure of Values' PLUS Volume 1, Chapter 3, Section 2 'The Means of Circulation'

In other words, aim to get up to the heading '3. Money' by Jan 14

Discuss the week's reading in the comments.

Use any translation/edition you like. Marxists.org has the Moore and Aveling translation in various file formats including epub and PDF: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/

Ben Fowkes translation, PDF: http://libgen.is/book/index.php?md5=9C4A100BD61BB2DB9BE26773E4DBC5D

AernaLingus says: I noticed that the linked copy of the Fowkes translation doesn't have bookmarks, so I took the liberty of adding them myself. You can either download my version with the bookmarks added, or if you're a bit paranoid (can't blame ya) and don't mind some light command line work you can use the same simple script that I did with my formatted plaintext bookmarks to take the PDF from libgen and add the bookmarks yourself.

Resources

(These are not expected reading, these are here to help you if you so choose)

-

Harvey's guide to reading it: https://www.davidharvey.org/media/Intro_A_Companion_to_Marxs_Capital.pdf

-

A University of Warwick guide to reading it: https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/english/currentstudents/postgraduate/masters/modules/worldlitworldsystems/hotr.marxs_capital.untilp72.pdf

-

Reading Capital with Comrades: A Liberation School podcast series - https://www.liberationschool.org/reading-capital-with-comrades-podcast/

@invalidusernamelol@hexbear.net @Othello@hexbear.net @Pluto@hexbear.net @Lerios@hexbear.net @ComradeRat@hexbear.net @heartheartbreak@hexbear.net @Hohsia@hexbear.net @Kolibri@hexbear.net @star_wraith@hexbear.net @commiewithoutorgans@hexbear.net @Snackuleata@hexbear.net @TovarishTomato@hexbear.net @Erika3sis@hexbear.net @quarrk@hexbear.net @Parsani@hexbear.net @oscardejarjayes@hexbear.net @Beaver@hexbear.net @NoLeftLeftWhereILive@hexbear.net @LaBellaLotta@hexbear.net @professionalduster@hexbear.net @GaveUp@hexbear.net @Dirt_Owl@hexbear.net @Sasuke@hexbear.net @wheresmysurplusvalue@hexbear.net @seeking_perhaps@hexbear.net @boiledfrog@hexbear.net @gaust@hexbear.net @Wertheimer@hexbear.net @666PeaceKeepaGirl@hexbear.net @BountifulEggnog@hexbear.net @PerryBot4000@hexbear.net @PaulSmackage@hexbear.net @420blazeit69@hexbear.net @hexaflexagonbear@hexbear.net @glingorfel@hexbear.net @Palacegalleryratio@hexbear.net @ImOnADiet@lemmygrad.ml @RedWizard@lemmygrad.ml @joaomarrom@hexbear.net @HeavenAndEarth@hexbear.net @impartial_fanboy@hexbear.net @bubbalu@hexbear.net @equinox@hexbear.net @SummerIsTooWarm@hexbear.net @Awoo@hexbear.net @DamarcusArt@lemmygrad.ml @SeventyTwoTrillion@hexbear.net @YearOfTheCommieDesktop@hexbear.net @asnailchosenatrandom@hexbear.net @Stpetergriffonsberg@hexbear.net @Melonius@hexbear.net @Jobasha@hexbear.net @ape@hexbear.net @Maoo@hexbear.net @Professional_Lurker@hexbear.net @featured@hexbear.net @IceWallowCum@hexbear.net @Doubledee@hexbear.net @Bioho@hexbear.net @SteamedHamberder@hexbear.net

It is not too late to catch up. I only started on Friday.

How far are you?

Thing is: this pace = the pace that gets the 3 volumes done in one year

Damn 1 was rough to finish on time, I was still on a trip away. But dat down today and blew through 20 pages and just loving it. Not much to mention, but I for some reason feel like I'm enjoying reading Marx (not just doing it for learning purposes with no joy) for the first time in this case. Let's goooo

Of course comrade, and of course the thanks is most deserved by you for organizing this (among others I think? But I can't remember usernames well lol)

I'm here 1 month later to say I did the same thing. I feel like I blitzed through most of chapter 3 today while then kids napped. Chapter 1 was a total slog, but coming out of that chapter was like exiting the Hyperbolic Time Chamber.

reporting in for posting duty o7

and yes, this week i have finished my communism homework on time!

I've been struggling to do one big post so i'm gonna try doing smaller posts instead (any more posts will be in replies to this one)

One of the neat things I've noticed about the earlier chapters is how well some of these basic, abstract commodity relations manifest in the larger historical scale. Quotes from Fowkes' translation.

The exchange of commodities begins where communities have their boundaries...However, as soon as productions have become commodities in the external relations of a community, they also, by reaction, become commodities in the internal life of the community.

This describes the process of the "innocent trade" stage of colonialism perfectly. At first, the goods traded are surplus goods, things not missed. In the fur trade, some of the earliest traded furs were actually old coats because the worn fur was softer, for example. As these furs are brought into relation with e.g. guns, textiles, etc one begins to see e.g. a buffalo and in it see not a collection of use-values, but instead only it's possibility of being exchanged for traded goods.

The constant repetition of exchange makes it a normal social process.

And henceforth the need for traded goods becomes a normal social need. This can be immediately practical, e.g. bullets once the gun is relied on, or it can relate to more social practices, e.g. the Ainu's use of Japanese goods in ritual.

In the course of time, therefore, at least some part of the products must be produced intentionally for the purpose of exchange.

I.e. one begins commodity production; the traded goods are no longer just surplus goods but goods produced specifically for trading.

The first chapter was really difficult to get through, especially the last section, I'm not sure if I was misunderstanding, but it felt like he was just repeating himself in different ways, I'm not sure he needed to use three separate paragraphs to explain the idea that the discovery of the theory of labour value didn't invent it, or change it's nature, just revealed it. Unless I'm just not comprehending it fully and I missed a major part of his arguments.

I have "read" Capital in the past, but upon re-reading it seems more like I skimmed it and skipped over parts that felt redundant, I'm trying to avoid that as much as possible now and it is really sticking out to me. Hoping chapter 2 helps clears things up a bit, I think I mostly get what he's saying, but I just don't understand his method of delivery very well. Could just be my modern sensibilities and own preferences as a writer.

it felt like he was just repeating himself in different ways

We all felt that

It was very grueling, especially restating the forms of value (which made me go cross-eyed). I think the main issue is that this is a foundational work, and so it has to be comprehensive, and also take baby steps to reach every point.

He started off with the most basic ideas and built up to a place that we all understand subconsciously. It all feels the same because it is such a basic understanding that people don't ever consciously think about it.

Its like if you explain your morning routine in excruciating detail it ends up taking longer than it would to do it all.

I think the first couple chapters made way more sense to me when I finished chapter 3 and then go over 1 and 2 again right away. Maybe not that they made more sense but the reasoning behind why he started there made more sense and that made what he was saying more interesting and processable.

It's alright. I prefer doing a lot of reading all at once as that's what I find it easiest to put in my schedule, rather than actually doing 6-7 pages every day and then putting the book down again. So perhaps that will also work out for you.

Even in the worst case scenario, you can just start reading whenever it's convenient for you (whether that's in a week or in six months) and you'll have the threads to look back on at least. If anybody right now is like "god damn it, I'm behind like 20 pages now and it's just gonna get worse and I can't catch up and--" then that is your brain tricking you, as the reading is challenging and it might not wanna do it. You can in fact do it and you don't have to "give up" and try again a year from now when the threads reset - you can just postpone it a few weeks or months for when you're in a better/less busy space. And think about how great it will feel at the end when you have actually read and (hopefully) understood Capital and have become an undisputed Marxist, no ifs, ands, or buts!

If anybody right now is like "god damn it, I'm behind like 20 pages now and it's just gonna get worse and I can't catch up and--" then that is your brain tricking you, as the reading is challenging and it might not wanna do it.

Hmmm good points I might need to frame it differently

PS: What I'll do is post the estimated time to catch up from 0 in each week's thread.

You can catch up by Sunday the 14th. Don't fall too far behind. Read 8-9 pages a day this week or whatever.

I'll be honest, some of the discussion in this week's thread especially on the emphasis on fiat money is concerning to me.

In order to be a rocket scientist, you have to start out with the fundamentals like simple forces, objects sliding down frictional planes, and Newton's law. If advanced physics presents things which appear to contradict the fundamentals, it is not necessarily because the fundamentals are obsolete. It remains to be proven that the fundamentals have actually changed in substance. Apparent contradictions emphasize the importance of fundamentals, because without them, the advanced topics are impossible to comprehend.

Likewise, fiat money is indeed an interesting topic — but it is not the principal question on which Capital rests. If fiat money is different from money as presented in Chapter 3, then it is because it is a further development of money that requires, in any case, an understanding of commodity money as a necessary prerequisite.

I am unconvinced fiat money is drastically different from commodity money. Chapter 3 has all the basic elements for understanding fiat money. I'll make an effortpost in the comments if I can, possibly later today.

In broad strokes:

- Token money (e.g. a pre-1971 US Dollar) is a commodity distinct from the metal it represents. This was true in Marx's time and is described in Chapter 3.

- Price and value are distinct. There is no necessity that the price of a US Dollar be equal in magnitude to its value. Their magnitudes are wildly divergent.

- All that changed when the US Dollar went off the gold standard is that the US Government no longer tied the price of the US Dollar to gold. This is very similar to Marx's comments in Chapter 3 about laws fixing the prices of gold and silver, or the ratio of their prices e.g. 15 to 1. If the US Dollar is now "free floating" it is only a legal recognition of the fact that the US Dollar was already a distinct commodity from gold.

All good points, but it should also be noted that (at least as I understand it) the US dollar is a commodity because it is the only thing used to buy/sell oil internationally (until recently).

In general the dollar is used as the "backbone" of most traded commodities, not just oil, though oil is obviously very important as it was (and still basically is) the major power source for all transportation on Earth. So I suppose it's a commodity in that sense, yes.

(though I think the biggest factor for the dollar's strength is that the dollar is backed by the Federal Reserve and various US institutions, which will do anything - including creating trillions of dollars out of thin air - to support it, while other countries (like China) would be much more nervous about that kind of financial wizardry. It's worth noting that others disagree on this view as the dollar as this very strong, vital force in the economy; Radhika Desai is essentially of the opinion that the dollar was never actually as strong as its proponents suggested, and that the history of the dollar since the end of WW2 has actually been weakness; stumbling from crisis to crisis as the US attempts to enforce it upon the world and is rebuffed)

Marx's use of the Bible is honestly really interesting. Expect to see more of it through Capital (and even more the earlier in his writings you go). It is inarguably the single largest literary, theoretical and philosophical inspiration Marx has throughout his life. Marx's library contained at least one copy of the Bible when he died, so it's also likely that it (like Hegel) was something he came back to time and time again.

Some more Marx-Bible facts:

In his early articles for the Rheinische Zeitung he refers, somewhat tongue-in-cheek, to both himself and other journalists as prophets and false prophets.

He closes his "Critique of the Gotha Programme" with a quote from the Bible identifying himself with Ezekiel.

He taught his daughters about Jesus as "the carpenter who the rich men killed", reciting his own version of the story himself.

According to the memoirs of German socialist Max Beer (who met Eleanor Marx), Marx rarely had much to say about religion in her memory except, when her mother and sister started going to Mr. Bradlaugh's secular Sunday services. This led Karl Marx to dissuade his wife and daughter from going there. Beer quotes Eleanor as saying: "[Karl Marx] told mother that edification or satisfaction of her metaphysical needs she would find them in the Jewish prophets rather than in Mr. Bradlaugh's shallow reasonings".

Some Jewish socialists have actually claimed him for the Jewish prophetic tradition, for example Abraham Shiplacoff's speech in the 1910s said (originally in Yiddish):

Marx was a prophet, no less so than Isaiah, Jeremiah, or Ezekiel. With honest conviction and courage he proclaimed the economic liberation of humanity. He appealed to the workers of the world and inspired them with his conviction that they are destined to fulfill the great task of abolishing poverty, thus putting an end to wars between nations and classes, and, in doing so, realize the great thousands-year-old dream of human brotherhood.

Marx's constant references made me curious so I looked into it, and the Bible has a shocking number of condemnations of poverty/oppression and outright critiques of markets, class, urban/rural divide, and so forth. The commodity-fetishism section from last chapter is especially neat because Marx secularises prophetic condemnations of idol worship, even using the same phrases (e.g. "work of their hands").

reciting his own version of the story himself.

The only good part of a christian upbringing is retelling the stories with all the hocus pocus ripped out and filling them with cuss words.

That's why I always love the story of the cleansing of the Temple. You don't need to believe in the supernatural to understand why Jesus would go absolutely apeshit on a bunch of loan sharks.

If he were alive in 2000 Jesus would have done 9/11.

"Jesus secretly resurrected and did 9/11" would be a fun conspiracy theory

If Marx was writing today, Capital would include stuff like "If by means of increased productivity the socially necessary labor needed to produce a pair of jeans is halved, then the value of those jeans also falls by half, as if Thanos had snapped his fingers at it."

Marx wrote about religion and especially Christianity a lot in the 1840s. Mostly about how it is an alienated form that dominates over the people whose minds produced it. Sound similar to commodity fetishism?

This footnote excerpt from ch1 is relevant to the money discussion in ch3. Marx was not a fan of utopian socialist proposals of labor money, or alternative money that avoids the pitfalls of abstract labor by counting directly as social labor. Eg. if you work for 1 hour you get a 1-labor-hour token.

”It may therefore be imagined that all commodities can simultaneously have this character [of money] impressed upon them, just as it can be imagined that all Catholics can be popes together.”

”It may therefore be imagined that all commodities can simultaneously have this character [of money] impressed upon them, just as it can be imagined that all Catholics can be popes together.”

I took that quote to mean you can't use everything as commodity-money, you have to set one aside (gold). How is that quote against labour-tokens?

[Edit: By labor money I mean something slightly different from the labor tokens mentioned in the Gotha Critique. Labor money would be a form of money within commodity production and private property, whereas the labor tokens mentioned in Gotha are referring to a post-capitalist society in which commodity production (i.e. private property) has been abolished.]

The rest of the footnote makes it clearer, as well as other writing in Grundrisse and Poverty of Philosophy. The so-called utopian socialists wanted to keep commodity production while eliminating money, whereas Marx thought that money is necessarily produced by commodity production and can't be done away with while keeping commodity production. So the connection between the Pope quote and labor money is simply that contemporary advocates for labor money wanted a situation in which all commodities could behave as money, which is what abolishing money effectively tries to do.

Full quote, bold added:

It is by no means self-evident that this character of direct and universal exchangeability is, so to speak, a polar one, and as intimately connected with its opposite pole, the absence of direct exchangeability, as the positive pole of the magnet is with its negative counterpart. It may therefore be imagined that all commodities can simultaneously have this character impressed upon them, just as it can be imagined that all Catholics can be popes together. It is, of course, highly desirable in the eyes of the petit bourgeois, for whom the production of commodities is the nec plus ultra of human freedom and individual independence, that the inconveniences resulting from this character of commodities not being directly exchangeable, should be removed. Proudhon’s socialism is a working out of this Philistine Utopia, a form of socialism which, as I have elsewhere shown, does not possess even the merit of originality. Long before his time, the task was attempted with much better success by Gray, Bray, and others. But, for all that, wisdom of this kind flourishes even now in certain circles under the name of “science.” Never has any school played more tricks with the word science, than that of Proudhon, for “wo Begriffe fehlen, Da stellt zur rechten Zeit ein Wort sich ein.” [“Where thoughts are absent, Words are brought in as convenient replacements,” Goethe’s Faust. See Proudhon’s Philosophy of Poverty]

The pope quote in Capital was probably borrowed from a section in Grundrisse ~10 years earlier, in a discussion on labor money

"Let the pope remain, but make everybody pope. Abolish money by making every commodity money and by equipping it with the specific attributes of money."

This is true elsewhere, but in interest of pedanticness I gotta point out that the Apocalypse quote is Marx using it's theoretical arguments to support his own, and in doing so (and a few other places in the book), he draws attention to Rome's similarity to English capitalism. Rather than dunking on Christians, here Marx is making an attempt to weaponise christians/ity against capitalism

Funny the guy selling bibles is the one buying brandy, too. What's going on in his life?

Yeah I thought that was funny too I get the feeling Marx was a bit of a shit poster.

Marx getting messy in the footnotes towards other writers confirms this for me

I imagine he’s a drunk, gourmand hustler like Jon Goodman in “o brother where art thou.”

Chapter 2, footnote 2. Proudhon creates his ideal of justice, of 'justice eternelle," from the juridical relations that correspond to the production of commodities: he thereby proves, to the consolation of all good petty bourgeois, that the production of commodities is a form as eternal as justice.

"Come out Proudhon, you petty-bourgeois bastard!"

"Come out Proudhon, you petty-bourgeois bastard!"My favorite fun fact about Marx is that when Proudhon wrote a book called "The Philosophy of Poverty" in 1846, Marx hated it so much that he wrote an entire book-length takedown of it, published in 1847, and called it, brilliantly, "The Poverty of Philosophy."

Don’t forget it also has the most savage foreword of all time (bolded the harshest part)

M. Proudhon has the misfortune of being peculiarly misunderstood in Europe. In France, he has the right to be a bad economist, because he is reputed to be a good German philosopher. In Germany, he has the right to be a bad philosopher, because he is reputed to be one of the ablest French economists. Being both German and economist at the same time, we desire to protest against this double error.

The reader will understand that in this thankless task we have often had to abandon our criticism of M. Proudhon in order to criticize German philosophy, and at the same time to give some observations on political economy.

Karl Marx Brussels, June 15, 1847

M. Proudhon's work is not just a treatise on political economy, an ordinary book; it is a bible. "Mysteries", "Secrets Wrested from the Bosom of God", "Revelations" – it lacks nothing. But as prophets are discussed nowadays more conscientiously than profane writers, the reader must resign himself to going with us through the arid and gloomy eruditions of "Genesis", in order to ascend later, with M. Proudhon, into the ethereal and fertile realm of super-socialism. (See Proudhon, Philosophy of Poverty, Prologue, p.III, line 20.)

More! less! not sufficiently! so far! not altogether! What clearness and precision of ideas and language! And such eclectic professorial twaddle is modestly baptised by Mr. Roscher, “the anatomico-physiological method” of Political Economy! One discovery however, he must have credit for, namely, that money is “a pleasant commodity.”

What a quote to end a chapter on. Particularly after getting into the weeds of how money was invented.

I love the part where he quotes Revelation to say money is the mark of the devil.

In the second place, a change in the value of gold does not interfere with its functions as a measure of value. The change affects all commodities simultaneously, and, therefore, caeteris paribus, leaves their relative values inter se, unaltered, although those values are now expressed in higher or lower gold-prices.

You can find out more about Marx's theory about how gold is used with its value in fetishistic form abstracted away from the physical gold, and how this can lead to higher prices, by searching for "inflation fetish"

We saw in a former chapter that the exchange of commodities implies contradictory and mutually exclusive conditions. The differentiation of commodities into commodities and money does not sweep away these inconsistencies, but develops a modus vivendi, a form in which they can exist side by side. This is generally the way in which real contradictions are reconciled. For instance, it is a contradiction to depict one body as constantly falling towards another, and as, at the same time, constantly flying away from it. The ellipse is a form of motion which, while allowing this contradiction to go on, at the same time reconciles it.

I kind of liked this part in chapter 3 section 2, but I never thought of contradictions like that, where things can just exist "side by side"

Yeah it's pretty cool. Usually analytical thought is heavy on logic which focuses on states, so a formal contradiction in logic implies an invalid state based on given definitions. But Hegel's dialectics focus on process instead of state. A contradiction is then a motor for change, a movement from one state to another.

The other nice thing about Hegelian dialectic for analyzing processes is that a contradiction can be investigated productively, whereas in pure logic, a contradiction is always negative: it negates the premises without positing something in their place, some new understanding of the contradictory premises and what makes them both true from different perspectives.

If anyone's wondering, Week 3 we will read the end of Ch.3 and all of 4 and 5

I would love if my epub reader program would display footnotes simultaneously with the main text. Basically the way footnotes are displayed on RedSails posts. I think that would be really nice for the footnotes in Capital.

We saw in a former chapter that the exchange of commodities implies contradictory and mutually exclusive conditions.

Wait what did we? Is he talking about the 'contradiction' between its use-value (to the buyer) and its exchange-value (to the seller)?

I think it's that and that for two commodities to be exchangeable they have to be the product of mutually exclusive private production.